ENCORE PRESENTATION: BILLY MEYER – A CAREER OF EXTREMES, PT. 2

Meyer admits his mistakes related to a grand plan to bring drag racing to the next level …

BILLY MEYER - A CAREER OF EXTREMES - PART 1

Originally published September 2008

Billy Meyer can’t help but wonder where the sport would be today if his plan to unify drag racing had worked.

He can’t help but wonder what might have happened if given the second chance to rethink his decisions at the time.

He wonders to this day why the rains chose to fall on the weekends he scheduled races as the president and owner of the IHRA.

The stories have circulated for two decades, some remotely factual and others downright inaccurate.

Twenty years later, he would like to set the record straight.

Truth be known, Meyer never had any intentions of becoming a sanctioning body president when the purchased the International Hot Rod Association from Larry Carrier.

In his eyes, purchasing the IHRA was the only way the sport of drag racing could truly become one.

In the end, his vision was not shared by all and he ended up running the newly acquired business. This was not the way the plan was supposed to transpire.

“Nobody is aware of the real story of what happened and why it happened,” Meyer said.

a d v e r t i s e m e n t

Click to visit our sponsor's website

Twenty years later, Meyer intends to tell that story.

Meyer said he made the purchase of the IHRA at the request of T. Wayne Robertson, then the head of R.J. Reynolds’ Motorsports program. Their vision was to bring the synergies together in one unified presence similar to NASCAR.

“His goal was to get the sport into one operating entity, they were tired of sponsoring both sanctioning bodies,” Meyer said. “He and I had talked about it and worked on it for a long time; he wanted it to be one system like NASCAR was.”

Winston sponsored both the NHRA and IHRA until the end of the 1986 season; then they stuck with only the NHRA.

Meyer’s proposal was the glue intended to seal them under the Winston banner.

Then the proposal was rejected. Not only was it rejected, but it was rejected with a vengeance and from that point forward Meyer’s new project took on an adversarial role against the NHRA.

The major drag racing press quickly embraced Meyer’s efforts. For the first time since the mid-1960s when the American Hot Rod Association’s Jim Tice innovated much of drag racing, an entity offered a similar potential. A strong IHRA would force the NHRA’s hand because the racers would have a viable alternative.

For those who worked with the Funny Car driver during his storied driving career, his brash statements and seemingly arrogant attitude didn’t endear him to many of those journalists or race officials. His understanding of how non-automotive marketing worked quickly erased any hard feelings.

When Meyer promised to take the sport to the next level he was taken very seriously by race fans and to a point, nervously by the NHRA. The media ate up the notion, after all he’d given all the reasons for them to believe in his vision.

His Texas Motorplex super track gave them all the credibility they needed in order to believe him.

Everything is sifted through God's hands, I don't know why it happens, I'm a lot better person for it, it taught me a lot, it sure has been beneficial that it happened.

a d v e r t i s e m e n t

Click to visit our sponsor's website

To tell the Motorplex story, the time machine must travel back to 1981 when Meyer lost a sponsorship.

“I was trying to figure out how to grow the sport bigger and better,” Meyer said.

Meyer did his best to assist the NHRA by traveling on the media tours hoping to drum any media support he could for the events.

He was the kind of successful young and fresh energy that then NHRA media directors Steve Earwood [now Rockingham Dragway owner] and Dave Densmore [now John Force publicist] needed to portray to the mainstream media.

Meyer had a confident swagger about himself.

He would detail how drag racing was still a leather jacket sport, except these leather jackets were other colors than black and cost upwards of $500.

For all of his work and efforts, in 1981, Meyer lost his sponsor after only one season and through no fault of his own.

Meyer carried major backing at the time from the United States Tobacco Company’s Skoal division and its president Lou Bantle opted to look into his company’s investment. He brought along his wife to the event.

The event just happened to be the NHRA Summernationals, then held in July, in Englishtown, NJ.

“He and his wife came to Englishtown in July and it was 104 degrees and they flew to the event in their Gulfstream airplane, easily a $20 million dollar investment,” Meyer said.

The primitive nature of the Englishtown facility was something drag racers had accepted as normal. This wasn’t the case for Corporate America.

“Back then there were no bathrooms, there were port-a-potties,” Meyer said. “Back then that race it was a big kind of a hang out campground race with bikers and a pretty rough crowd back in that time. Mrs. Bantle had to stand in line at a port-a-potty with a bunch of biker girls at the time, pretty rough crowd, heat hanging and no place to go it was 104 degrees. They never came back and I couldn't renew that sponsorship after that. That's the only sponsorship I've ever had that someone left me and only lasted one year. They went back to NASCAR.”

That day, the vision for the Texas Motorplex materialized.

This would be the nicest facility in all of drag racing complete with a concrete quarter-mile, huge wrap-around tower with plenty of race suites. What the Orange County International Raceway tower was to the 1970s, Meyer’s Texas Motorplex would be to the 1980s.

Every part of the facility was ahead of its time.

Meyer actually bought two parcels of Texas land, the current one in Ennis and another in Terrell. He was intent to build his facility in the city which would work with him the best. In the end it was Waco.

The Texas Motorplex debuted in 1986 to much fanfare and was everything a drag racing fan could hope for.

When the IHRA opportunity presented itself, the Motorplex still had the “new” smell to it.

a d v e r t i s e m e n t

Click to visit our sponsor's website

The presentation blow up was something Meyer didn’t plan for. The rejection wasn’t the end of his world either. It only inspired him to succeed.

From that point, the Meyer versus NHRA scenario became a game of one-upmanship. The NHRA issued a press release after the meeting which quoted Wally Parks, Chairman of the Board for the NHRA.

“We feel drag racing is too important to be controlled by one man,” Parks said.

The media mocked the statement as Parks had filled the role for much of drag racing’s existence.

Meyer had the media in his pocket at this point when the battle lines were drawn.

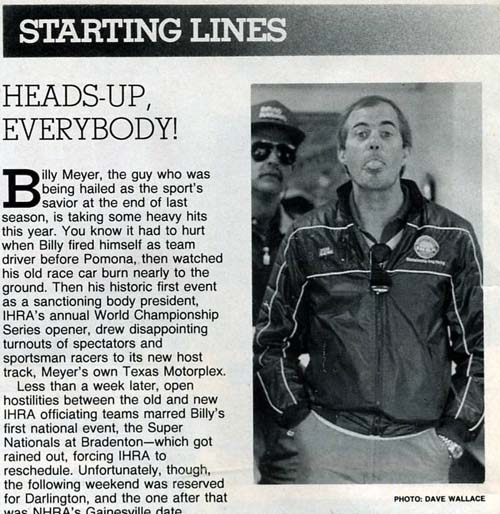

The overwhelming desire to get back at the NHRA forced Meyer into the first of what would prove to be several tactical errors in judgment.

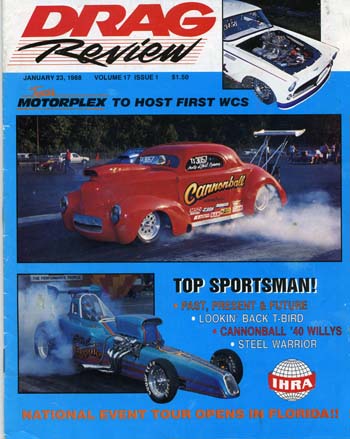

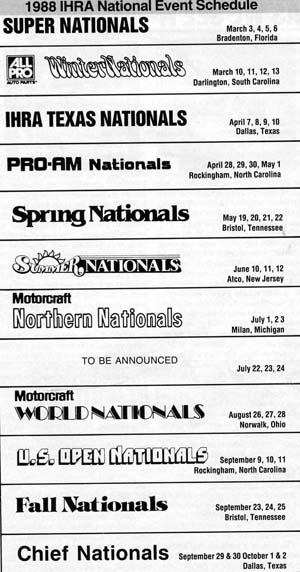

During the SEMA press conference, Meyer proclaimed in his announcement the IHRA would sanction at least twelve races in 1988, this coming on the heels of an eight-race season.

The statement would end up costing Meyer dearly.

Meyer’s team scrambled until just weeks before the season to fill the dates.

In the midst of this search, the IHRA Headquarters were relocated to Waco, Texas from the traditional Bristol, Tenn., location.

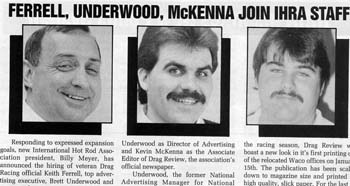

Meyer brought in a strong team of management types including Keith Ferrell, Bob Devour and Brett Underwood.

On paper the organization looked to be headed in the right direction.

In the pits and in the shops, the racers just weren’t on board with the new owner.

Scheduling 12-races was a tactical error that could be overcome, but with just weeks before the season-opener in Bradenton, Fla., Meyer announced the sportsman program would be drastically altered.

Meyer completely dispersed the notion of traditional class racing and replaced this cult of sportsman following with indexed back racing ranging from 7.90 to 12.90 seconds. This decision was made with no discussion with the racers and very little with his vice president Ted Jones, who had run the IHRA nearly from the first year.

The gear-heads became his first enemy.

a d v e r t i s e m e n t

Click to visit our sponsor's website

Meyer’s decision led to an all-out revolt from the racers who had their purpose-built race cars essentially obsoleted with no grounds for protest.

His Drag Review column merely stated, “It’s simple, pick an index and go racing.”

Such a statement didn’t bode well for dyed-in-the-wool class racers who had meticulously built their classic cars to certain specifics. Those estranged racers, who with corporate backing from Moroso Performance left the IHRA to form the Sportsman Racers Association.

Not everything was a negative in regards to the sportsman revamp. He kept the Top Sportsman division intact as well as its highly popular Saturday evening Quick Eight, as well as creating a new Junior Pro Stock division dubbed as Factory Modified.

The only professional division changed was the traditional mountain motor Pro Stock division in an attempt to unify this style of racing between the sanctioning bodies. Instead of a pure mountain motor format, NHRA 500-inch cars were allowed to compete at traditional weight while the big-inch engines were forced to bolt on extra weight. This was the only hope Meyer had to attract factory support.

Extra races, sportsman and professional divisions both totally revamped and a freshly relocated staff, the drastically different IHRA prepared for battle.

Then it rained.

It rained some more.

Rains fell to the point that eleven of twelve races on the tour were impacted negatively by rain. Eight of them required rescheduling.

None of the previous miscues would affect Meyer in the way the rain would. He could have worked his way through the previous situations but weather killed his efforts.

A downtrodden Meyer tried his best to interject humor into the situation by suggesting in an article published by Petersen’s DRAG RACING magazine; “If you know anywhere that’s suffering from a drought, just let me know, I know how to make it rain anywhere,” Meyer said. “We’ll schedule a race and I’ll guarantee you that it will rain.”

The IHRA was jokingly referred to as “It Has Rained Again”.

A promoter knows all too well rain can break a season and for Meyer, according to a DRAG RACING magazine article, his losses totaled upwards of $2.5 million dollars.

In an extreme case of Murphy’s Law, Meyer was stricken at his crown jewel Texas Motorplex.

Meyer offered a $100,000 bonus to any professional racer who could win two of the three events at the Motorplex. This was an effort to boost entries at this facility.

At the final event of the season, a rain-delayed marathon minus a strong spectator showing meant Meyer had to fork over the financially-tough bonuses to Ed McCulloch and Warren Johnson.

Adding to the other headaches, was a sportsman/bracket racing publication operated by Becky White who continually took Meyer to task for his actions/miscues and a well-publicized feud with Pro Stock legends Bob Glidden and Reher-Morrison after both refused teardown by race officials.

Along with Glidden, following the dispute at the Motorcraft Northern Nationals in Milan, Mich., Reher-Morrison also pulled out of IHRA and has never returned to this day.

Glidden and Meyer eventually became embroiled in a bitter, mud-slinging campaign in the media which led to lawsuits on both ends.

Meyer was faced by another significant challenge at the end of the season. Many of the IHRA’s regular national event tracks were openly revolting against the Meyer regime.

According to a Petersen’s Drag Racing magazine article, Meyer was so tired of the hassle and feeling the financial pinch, he entertained buy-out offers by those tracks looking to leave.

In the end, the buyout offer that worked the best for Meyer was the one where Jim Ruth offered to buy the IHRA back from Meyer.

a d v e r t i s e m e n t

Click to visit our sponsor's website

If you’re looking for a debate from Meyer regarding his decisions, you won’t get one. Meyer has spent two decades since

acclimating himself to the intricacies of sportsman racing and admits he’s continually refining his programs at the Texas Motorplex.

However, the luxury of being able to look back without pressure suggests Meyer was well ahead of his time.

The initial vision Meyer said he and Robertson shared wasn’t far off from what the HD Partners proposal presented in their failed attempt to purchase the assets of the NHRA. The HD Partners would manage the professional assets while there would be a separate sportsman racing entity.

By all accounts the initial proposal by Meyer should have been accepted; at least that’s how Meyer sees it.

“I bought IHRA and then went to NHRA with the complete proposal, we had attorneys and a complete business presentation,” Meyer recalled. “The presentation was written by T. Boone Pickens, who is one of the most successful businessmen in America.”

The plan detailed how to merge the two sanctions into one.

“We were going to try and create two entities out of the NHRA,” Meyer explained. “One was going to be a for-profit operating company. You could have called that the NHRA. The for-profit company would handle all the licensing and the national event operations as well as the sportsman racing. Our group would have bought that portion from the NHRA. The group would have bought the NHRA-owned tracks and the Texas Motorplex would have been part of the deal. All of the national event contracts would have been included as well.

“This was the same kind of plan as the H-D Partners proposal. I brought the plan knowing I could bring the IHRA to the table. We would have taken all of the NHRA and IHRA national event contracts and put them into a for-profit corporation. We would take all of the tracks owned by the parties involved and put into that for-profit corporation.

“If you’re going to buy those properties, then that’s going to put a lot of money into the original not-for-profit corporation not owned by anybody. That money would become like an endowment similar to those colleges operate on. That endowment would operate the original NHRA which would have paid the retirement to the original people, and would fund the safety aspect and the original 501C non-profit organizational charter.

“The original non-profit NHRA would stay in existence. They would essentially oversee the safety and rules portion of the sport.”

The for-profit corporation would have owned everything right down to the in-house publication National DRAGSTER.

Hindsight being 20/20, Meyer said he’s a better man for the IHRA experience. There will be those who will always remember his IHRA efforts, and some Meyer admits will always have bad feelings towards him.

“There are some people down there that still don’t like me to this day,” Meyer admitted, discussing the Carolinas and their disdain for him related to his decisions made in class racing.

In the end, Meyer admits his presentation of the initial program made all the difference. He said his attitude could have been easily misconstrued as being cocky.

The ego of those involved took what was aimed as a positive and moved in a negative direction.

“Maybe if I would've been more relaxed with the way I approached things back then it would have come off different,” Meyer admitted. “Everything is sifted through God's hands, I don't know why it happens, I'm a lot better person for it, it taught me a lot, it sure has been beneficial that it happened.”

Meyer never had a “Plan B” for his proposal because he felt it was such a sure winner for the NHRA and all of the parties involved. He’s simply accepted what has happened and moved on.

“It would've been a very positive thing for the sport and Winston would've been behind it,” Meyer added. “That being said when they turned down our proposal I had bought a business and no clue how to operate it but I was gonna do it the best method it could. It is what it is and it's long gone but it did get NHRA thinking at a more promotional way.”

The big question is; will the NHRA make the same mistake again.

This time Billy Meyer will sit back and watch.