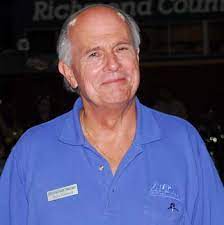

STEVE EARWOOD REFLECTS ON STORIED DRAG RACING CAREER IN RETIREMENT ANNOUNCEMENT

Steve Earwood’s office was cluttered, but not to the extent it had been for decades.

Steve Earwood’s office was cluttered, but not to the extent it had been for decades.

He’d spent the first week of November clearing out and packing up in preparation of relinquishing the ownership reins. He’d been behind the massive desk for 30 years and eight months, transforming Rockingham Dragway from a track that opened only twice a year to one that was in operation almost year-round with motorsports events and testing, concerts, and more.

By now, the multiple piles of race flyers, magazines, photos, diecast cars, and a couple of Bibles had been reduced to something far more manageable. The time had come to vacate the premises and hand the keys to new owners Al Gennarelli and Dan VanHorn. And beyond an impending trip to the West Coast, the 74-year-old Earwood hadn’t a clue what was on his horizon.

“I have been swimming with the sharks for 30 years, and I’ve learned not to spend a lot of time on the regrets from the past or the anxieties of tomorrow,” he said. “I have learned to focus on today. All we can control is today.”

And that cabin he had for decades planned on retiring to in the north Georgia mountains? Well, plans change.

“There are just so many things from living in Southern Pines all these years,” he said. “I can call my doctor on his cell phone and say, ‘My knee hurts,’ and he’ll say, ‘Come see me tomorrow.’ I can call a restaurant, they recognize my voice and say, ‘What time do you want your table, Mr. Earwood?’ Those things, in my old age, mean something.”

It took Earwood nearly 20 years – he was then in his mid 40s – to bring his dream of dragstrip ownership to fruition, but his interest in drag racing had begun when he was a young teen and avid reader of ‘Hot Rod’ magazine. It was in that publication that Earwood became entranced by the editorials of Wally Parks, who had co-founded the magazine in 1948 and who launched the National Hot Rod Association three years later. Earwood told his mother, “When I grow up, I’m going to work for that man.”

He would, but not before first managing Gainesville Raceway and then operating his own Pro Stock circuit in the Southeast. He wound up working for Parks and NHRA drumming up media coverage of national events – and did it with such success that Billy Meyer hired Earwood to manage his new Texas Motorplex. That was followed by a stint at the helm of Atlanta Dragway, then a return to the Motorplex.

He would, but not before first managing Gainesville Raceway and then operating his own Pro Stock circuit in the Southeast. He wound up working for Parks and NHRA drumming up media coverage of national events – and did it with such success that Billy Meyer hired Earwood to manage his new Texas Motorplex. That was followed by a stint at the helm of Atlanta Dragway, then a return to the Motorplex.

All the while, the dream of owning his own track gnawed at him.

“I really got the itch because I had made a lot of guys a lot of money. And I thought, ‘You know what? I want a seat at that table,’” Earwood said.

That led him to informally inquire about purchasing Rockingham Dragway, which at the time was an underutilized facility across U.S. 1 from North Carolina Motor Speedway, which hosted two NASCAR weekends a year. The stock car oval opened in 1965, followed five years later by the dragstrip, which initially hosted AHRA events. It soon became a staple on the upstart IHRA circuit along with Bristol and Darlington, and Rockingham annually hosted the Pro-Am Nationals and U.S. Open events – but that was the extent of the drag racing program there.

One day, Earwood picked up the phone and called Frank Wilson, who was the president of the NASCAR track and the dragstrip.

“I said, ‘If Rockingham ever comes available, I’d like to talk about purchasing it.’ Well, I had no money – I mean, no money – back in those days,” Earwood said. “They sent word to me – sent a gal to look me up at the national event at Houston when I was at the Texas Motorplex – to say they wanted to talk to me about buying it. I said, ‘Well, I’ll be in the Southeast because I’d take my favorite aunt to church on Easter Sunday every year. So after I did that, I drove up from Georgia and met them. I had no money, and they wanted way too much money for it anyway.”

While he was in the Sandhills region of the state, Earwood decided to take an hour’s drive and pay a visit to one of his former Pro Stock-circuit regulars, Roy Hill. He explained to Hill his desire to purchase Rockingham Dragway, and that he didn’t have the means to see it to fruition.

“Roy, being Roy, said, ‘Let’s buy it!’ I said, ‘It’s not that easy,’” Earwood recalled.

After returning to Texas, Earwood got a call from Hill asking if he could get involved, and given the go-ahead, Hill had found a venture capitalist in High Point, N.C., in Cliff Stewart. Stewart, who had fielded a NASCAR Cup team on a limited basis for some two decades, agreed to fund the down payment, and with that promise and nothing more in hand, Earwood quit his job at the Motorplex and moved into a small apartment in Aberdeen, N.C.

Plans to close the deal were set for a Monday, but on the preceding Friday, Hill called Earwood to break the news that Stewart had decided against completing the deal.

Earwood and Hill spent the weekend calling bankers across the state in search of a loan. They finally found one bank whose manager had the ability to loan $10,000 to any person with minimal guarantees, and on Monday morning, 28 investors walked into the bank to borrow $280,000. Hill ponied up the remaining $20,000, and Earwood had his hands on the track at last.

There was no time for celebration, as the 1992 NHRA Winston Invitational was only 34 days away. It went off as planned, and Earwood was on his way to a three-decade-plus run as owner.

But there were times along the way that the dream was more of a nightmare that tested Earwood’s resolve.

“After about a year, I think he started to second-guess himself,” said Dave Densmore, Earwood’s closest friend and longtime NHRA publicity partner. “But he wound up loving it. He thought he was going to love it, which is the only reason he did it, you know? All those years that he had worked for someone else and NHRA, he was gathering information. He had ideas about why this would work or that would work when it didn’t for somebody else, and I think he applied those lessons to Rockingham when he got there.”

It was during that first year of ownership that Stephanie Peterson, Earwood’s daughter, saw first-hand how tough things could be for him.

It was during that first year of ownership that Stephanie Peterson, Earwood’s daughter, saw first-hand how tough things could be for him.

“Jason (Peterson) and I got married in January of ’93, and I just remember that my father didn’t have two nickels to rub together,” she said. “And here his only daughter’s getting married, and we had this beautiful wedding – and I felt kind of guilty, honestly. Being the only child, my parents were very generous with me, and I didn’t take that for granted. I’ve always said my whole life that I was spoiled, but I was not a brat and there is a difference.

“So, here he was, struggling, immediately after he purchases the track. He has the Winston Invitational, and, yes, those were glorious days and they were beautiful, but there’s also a lot of expense that comes with that. Even just getting the track up and running to where they could open every weekend was a huge investment. There were times – and they weren’t often – but definitely several times over the years that I asked Jason, ‘Should we send my father some money?’”

Earwood said “a burning desire” for track ownership had led him to take that huge financial leap despite the potential downsides, adding that learning to “ignore the negatives and focus on positives” allowed him to stay the course. “If the positives are 51%, go with it. It ain’t a perfect world,” he said.

There was a time when Earwood was so overwhelmed by the workload that he was ready to torpedo his dream and literally give his piece of the track to Hill. That’s when another pair of drag racers, Johnny and Charles Dowey, bought out Hill’s stake in the track – and eventually, Earwood was able to take a similar course and gain complete ownership.

During that period, Earwood managed quite well thanks to two NASCAR events a year. How so? He owned all the property across the highway from the speedway, and thousands of people paid to camp there, park there, and set up souvenir stands. Those races were a guaranteed source of income through 2003, when the sale of the speedway brought with it the loss of one race date. In early 2004, NASCAR Cup competition was held there for the final time, cutting off that revenue stream for Earwood.

But he had long planned for that inevitability, scheduling non-motorsports events such as Rugged Maniac obstacle-course races, and concerts featuring artists such as Metallica, Kid Rock, String Cheese Incident, Judas Priest, Tool, Korn, and Foo Fighters. The track annually hosted Top Fuel Harley competitions, bike rallies, Super Chevy Show events, and more. Rockingham Dragway was there for upstart sanctioning bodies such as ADRL, XDRL and PDRA. The inaugural ADRL race was such an immediate hit that the North Carolina State Highway Patrol had to turn away fans because the venue had exceeded capacity.

Earwood’s resilience and foresight surprised even his best friend.

Earwood’s resilience and foresight surprised even his best friend.

“To think that he’s been there for 31 years is incredible,” Densmore said. “I never really thought he would adapt to the changing drag racing landscape as he has. Trends have changed over the last 31 years, and he’s always managed to roll with the flow. That’s been one of the biggest secrets to his success, for sure.”

Stephanie Peterson said it was a blessing that her father had the Winston Invitational at the track almost before the ink on the sales contract was dry. It was, she said, “like having the Super Bowl at his track, with all the stars there and the stands filled on both sides. And then it went away, and the NASCAR races, and Rusty Wallace and all the NASCAR guys flying their jets and helicopters in and landing at the dragway. He felt like the carpet was being pulled out from under his feet, but he rebounded every time with a great attitude, hard work, and innovation when most people might have said, ‘This is too much.’”

The secret, Earwood said, is managing priorities, and his approach to that is simple.

The secret, Earwood said, is managing priorities, and his approach to that is simple.

“Every day I come in here to the office I’ve got a legal pad of notes of things to accomplish. I go over that legal pad and whatever makes me money gets my attention,” he said. “That’s what I work on, whether it be romancing the Street Outlaws people to get their event, which we finally did, or the NMCA, which I romanced and bothered and irritated for 12 years and finally got it. It’s about looking into the future as far as what makes this thing money.

“This is like running a small city. I have plumbing problems, electrical problems, security problems, employee problems, lawsuit problems, insurance problems, paying the light bill problems. So you’d better focus on all that stuff instead of sitting here dreaming how long this is gonna last.”

So how has Earwood measured his success as a track owner? Again, it’s simple: The bottom line.

“I didn’t go to the Wharton School of Business, I don’t do any projections, ” he added. “I know race track owners who do these projections, and they say, ‘We’re going to make this much money.’ How do you know that? You don’t know that. You don’t know what the weather’s going to do or if anybody’s going to show up or not.

“So I just focus on getting the football into the end zone any way we possibly can, and then on Monday morning I can tell you how we did. People say, ‘How’re you doing?’ I say, ‘I don’t know, but I can tell you Monday’ because my controller gives me a spreadsheet Monday morning and tells me to the dime.”

With Rockingham Dragway having long ago become a major motorsports venue, it’s only logical that others would want to take it off Earwood’s hands. He said he learned from 16-time Funny Car champion John Force how to separate the tire kickers from the serious suitors.

“Force told me that people would come up to him saying they wanted to sponsor him, and all they’d really be doing was wasting his time. So he would say, ‘Give me a hundred bucks and your phone number and I’ll call you back.’ And he never got a hundred bucks,” Earwood said.

“When people would approach me, I’d say, ‘Send me $40,000 and we’ll talk.’ One guy took me up on it, then it fell through and I kept his money. I didn’t want to sell it to just anybody because I want to see it stay a dragstrip. This dragstrip is very important to this county. It lost the tobacco industry, the textile industry, NASCAR races at the speedway, so my stock has risen exponentially because of that. We bring a lot of people through here from out of town, out of state, and they come in and spend money and leave – and we don’t have to educate their kids. So this is a great thing for Richmond County, and Richmond County’s been awfully good to me.”

The purchase agreement with Al Gennarelli and Dan VanHorn was announced in 2020, with the Richmond County Daily Journal reporting that the sale price was $1.85 million.

The purchase agreement with Al Gennarelli and Dan VanHorn was announced in 2020, with the Richmond County Daily Journal reporting that the sale price was $1.85 million.

Earwood is confident that the new proprietors are going to sustain what he’s built and then some.

“They’re going to improve on what I’ve done over the years,” he said. “When they came along, I got pretty serious and they got pretty serious, and they gave me a pretty substantial deposit. Dan had the Modern Street Hemi Shootout series, 12 to 14 events a year, and came here with it. I worked around him and liked the way he handled himself around racers and track operators. They have the basic fundamentals it takes and the financing.”

Gennarelli and VanHorn will find out what Earwood learned a long time ago; that weather dictates fiscal success or failure. Jason and Stephanie Peterson found that out first-hand, too, when they were hired to run U.S. 131 Motorsports Park in Martin, Michigan.

“A wet spring or wet summer is very detrimental to our business,” Stephanie said. “Our business is dictated by the weather, not only what happens on race day but what the weatherman forecasts. If you get a poor forecast, people have already made their plans what they’re doing. We still have all the expenses: advertising, bringing in racers depending on what type of event it is, your track staff, if you do have the race do you have the staff to dry it, and there’s hardly anyone in the seats. It’s real hard to make payroll and pay your bills when it’s like that.

“The crazy part of our business is there are so many great times. When the good times are good, they’re good, but when they’re bad, they’re really bad.”

Fortunately, the weather in 2022 has meant a good swan-song season for Earwood. His final race was a dual AHDRA/AMRA event featuring Top Fuel Harleys, and he took the microphone in the tower to call the final round Oct. 30. He had expected to have butterflies or some sort of emotional tug, but said it felt like it was “just another day on the job” – until the race was over and VanHorn asked to walk with him from the office to the tower.

“We’re almost to the tower and he said, ‘Al and I want to talk to you about something.’ So we’re climbing the steps in the tower, and I’m thinking there’s something going on with closing the sale,” Earwood said. “I’m thinking, ‘What am I willing to compromise on? Am I willing to restructure the payout?’ And as I’m about to open the door, i thought, ‘Lord, give me the wisdom to listen and not respond.’ And I open the door, they turn the lights on, and there are 50 people in there – my girlfriend had been planning this surprise going-away for I don’t know how long.

“That meant something to me. That was a perfect cap for 30 years and eight months being here.”

Now what? At long last, what’s next?

For one, he said he’s going to set up shop in an office he has in Southern Pines “because I don’t want to drag all this junk in my house.” And as he glanced down, he murmured, “I’ve got to make sure that I grab that shotgun that’s been laying there at my feet for 30 years.”

Beyond that and a consulting role with Rockingham Dragway’s new owners, he’ll help with events in the warm months at U.S. 131, much to the delight of the Petersons.

“We wouldn’t be in this business if he weren’t in it, and that’s very much a positive thing,” Stephanie said. “There are times Jason talks to him more than I do, and I talk to my father almost every day.

“I just love having that in common and being able to bounce ideas off of him. Or Jason thinks something and I think another, and I’ll say, ‘Well, let’s call and ask my father,’ and there aren’t too many spouses that would want to keep hearing that this many years later. He’s very good, and Jason totally gets it.”

Beyond that, Earwood said he hasn’t a clue what his future looks like.

“People ask what I’m gonna do after 300 days. I say, ‘Ask me in 301 days because I do not know,’” he said. “I have not made any plans for what happens now because it’s a waste of time. I’ll see what each new day brings.”