GWYNN’S HISTORY, PRECIOUS MEMORIES ON BARRETT-JACKSON AUCTION BLOCK

Darrell Gwynn can picture it now.

Darrell Gwynn can picture it now.

The crowd will go crazy, he said.

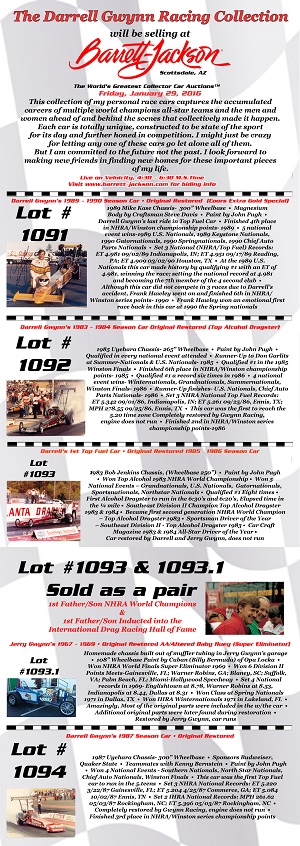

Car enthusiasts will cheer when his dad’s fuel altered, the one that carried Jerry Gwynn to several strategic victories and the 1969 NHRA Super Eliminator championship, comes roaring up onto the block Friday, Jan. 29 at the Barrett-Jackson Auction at Scottsdale, Ariz.

“Let me tell you, when he drives that thing up onstage, the walls are going to rattle. And they’re going to get on their feet when ol’ Baby Huey crosses the block,” Darrell Gwynn said.

For a flash, the Gwynns will feel a sentimental swell. They’ll marvel that the homemade chassis made out of muffler tubing in the family garage blasted to the winners circle a number of times and set records at the likes of Englishtown and Indianapolis. They’ll admire the blue paint job with the comically oversized image of the “Baby Huey” cartoon duck, complete with bonnet and diaper and bow tie. And they’ll beam that this restored race car has most of its original parts. But mostly in those fleeting seconds, the happy times will flash before their eyes, and they’ll remember the journey more than the destinations.

It will happen again and again and again between 4:30 and 6:30 that evening as three vehicles – one of them Jeff Gordon’s first NASCAR ride, the Hemi-powered “Baby Ruth” ’66 Dodge Charger – go up for bid on behalf of charity.

And they’ll feel a tender twinge, a pang of poignancy, when their five personal cars –– including two Top Alcohol dragsters and Darrell Gwynn’s storied and star-crossed Coors Extra Gold Special Top Fueler – roll into the arms of a stranger.

But it is time, time to let go.

Darrell Gwynn has sensed that for months.

“As you know, there’s no retirement fund in drag racing,” he said, calling this parting with the palpable part of his beloved history “my last hurrah.” Said Gwynn, “As bittersweet as it is – I hate to see these cars go – I’m selling my building. It’s time.

“I treasure them. I used to look at them every day,” he said of the cars, knowing they hold a huge spot in his heart but at the same time knowing they’re mere “things” just the same. He said, “It just comes a time in life when you’ve got so many assets and you’ve got so much crap and you say, ‘Wait a minute. What am I doing with all this stuff?’ Hopefully somebody else can enjoy the memories.”

The cars are just part of what Gwynn is giving up.

He has folded his foundation into The Miami Project To Cure Paralysis. The organization just marked its 30th year of spinal-cord injury research and efforts to find new treatments for paralysis resulting from spinal cord injury.

That’s a cause Gwynn has long supported, even before his April 15, 1990, exhibition-race accident in England that left him paralyzed from the chest down and cost him a significant portion of his left arm.

He said he has “basically gone back to The Miami Project after supporting them with my Coors Extra Gold car. We placed a decal on the car with their logo on it when we were doing well and kicking ass, raising a lot of money for The Miami Project.”

After his own accident, Gwynn and his family formed the Darrell Gwynn Foundation, which focused more on helping spinal-cord injury patients cope with daily functioning than actually curing the condition. He has presented dozens of wheelchairs to deserving individuals through the past several years and raised awareness for the cause at such events as NHRA track walks. But the responsibilities became greater than he can keep up with.

So he decided to morph it into the Darrell Gwynn Quality of Life Chapter of The Miami Project. Many of the foundation’s programs will continue as he joins the Buoniconti Fund to Cure Paralysis. Miami Dolphins linebacker Nick Buoniconti and son Marc are co-founders of The Miami Project, after Marc Buoniconti, playing football for The Citadel, suffered a spinal-cord injury while making a tackle in 1985 that rendered him a quadriplegic. The Buoniconti Fund is the non-profit fundraising vehicle for The Miami Project.

“The Darrell Gwynn Foundation just became so much work for me that I just decided I need to slow down a little bit,” Gwynn said. “So I merged the organization so to speak, with The Miami Project.”

And he’s hoping the word will spread about his offerings that will be up for sale, especially with no reserve on any of his cars.

“We’ve got our you-know-whats on the line. We’re trying to do our due diligence to make sure these cars get a good home, No. 1, and that somebody doesn’t steal ’em, No. 2,” Gwynn said. “In the auction business, it takes two people to want those cars. If we’ve got one, we’re in trouble. If we’ve got two, we’re OK. It takes two [bidders]. It takes a good time slot, which we have. It also take a couple of people who want it . . . a little bit of lights and camera . . . And enthusiasm doesn’t hurt anything.”

He’s selling three vehicles for The Miami Project, charity cars, at the Barrett-Jackson Auction. The one that has captured a fair bit of attention is Gordon’s “Baby Ruth” classic in which the now-retired NASCAR star won his first three elite-level trophies.

He’s selling three vehicles for The Miami Project, charity cars, at the Barrett-Jackson Auction. The one that has captured a fair bit of attention is Gordon’s “Baby Ruth” classic in which the now-retired NASCAR star won his first three elite-level trophies.

“It’s making lots of noise across the country,” Gwynn said. “The original chassis builder and original engine builder restored it. Jeff Gordon’s dad [stepdad John Bickford] went by and saw the car during the holidays and texted me. He said, ‘This car is pristine, man. You guys did a wonderful job.’ We’re hopeful to raise a lot of money for the Darrell Gwynn Chapter with that car.”

Also going to the charity are proceeds from the sale of a minibus.

“I’m also selling five personal cars: four of mine, one of my dad’s. My dad’s car – the one he won the championship in – and the car I won my [1983 Top Alcohol Dragster championship] in are being sold as a pair. Because of Dad and I being the first father-son world champions in the NHRA and the first father-son in the [International Drag Racing] Hall of Fame, we thought we’d sell them together.”

Of course, he’s hoping these cars will fetch some massive dollars for his noble cause. But he said he has no idea what a fair price would be: “I really don’t know. That’s hard to say. To me, they’re worth millions, because of the memories that are behind them.”

Oh, those memories . . . They’re not just about elapsed times and records and victories.

“As a kid, I traveled all across the country with my dad. My dad raced. My dad became world champion, was Division 2 champion many times, and won some national events. As a kid in high school and junior high and elementary school, I got to live that life,” Gwynn said.

“Big Daddy [Don Garlits] used to spend the night at our house when he used to come down and race at Miami-Hollywood. And I couldn’t sleep at night, knowing Big Daddy was in the next room. I was about eight years old. And here are some of the cars that gave Big Daddy a rough time,” Gwynn said, referring to his assortment of Barrett-Jackson vehicles.”

Gwynn admittedly still buys into the romance of the early days of drag racing. They’re his happy childhood memories and snapshots of the rising star he was.

“There’s nothing like NHRA racing in the ’60s, ’70s, and ’80s,” he said. “They’re trying to do some great things now to make the sport great. But I don’t care who you ask, the ’60s, ’70s, and ’80s were the best years. And that’s where these cars came from.”

Conversely, those cars are what lured Gwynn and the Coors Extra Gold Special Dragster is the one in which Gwynn rode out his devastating accident. But he harbors no bitterness.

“The good outweighs the bad, kind of like 99.9 percent good memories and a little bit, a half a percent, of bad memories,” he said. “Certainly, when you look at that Coors Extra Gold car [it reminds me of] when I was at the top of my game and we had a great partner in Coors. Things were going our way. We were winning races. Just got through winning the Gatornationals in 1990, in March. Then April 15th the same year is when I got hurt.

“This car represents so much,” Gwynn said. “It’s the car that came back the very first race after missing three races, with Frank Hawley behind the wheel. Won the Springnationals.

“If you just sit down and think about each and every car and what it represents, there’s a lot of history there. I’ve been getting some e-mails from a lot of people who said, ‘Oh, my gosh, Darrell – Not only are you making me feel old, but there’s some great memories behind these cars. I remember this and I remember this . . .’ It’s fun kind of reliving all of that, because that’s what life’s about.”

It’s about having fun looking back. It’s also about planning for what’s ahead.

For the immediate future, Darrell Gwynn’s mind will be on presenting these cars at their best for maximum yield at the Barrett-Jackson Auction at Scottsdale. After that, with a bit of weight lifted from his shoulders, Gwynn will continue launching and maximizing quality of life initiatives and keep aiding The Buoniconti Fund in its role to raise money and awareness to support The Miami Project to Cure Paralysis.

But the roar of the crowd next weekend is something Gwynn is anticipating hearing once again.