ENCORE PRESENTATION: BILLY MEYER – A CAREER OF EXTREMES - PART 1

Originally published September 2008

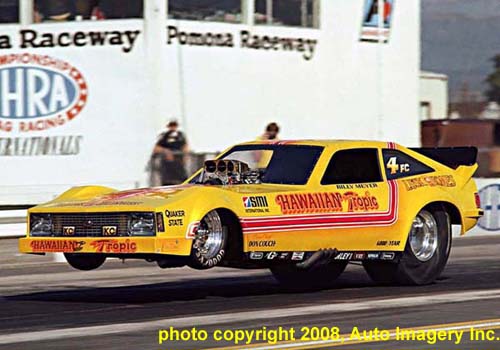

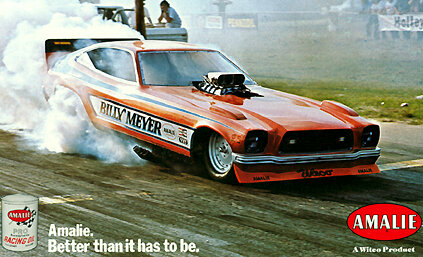

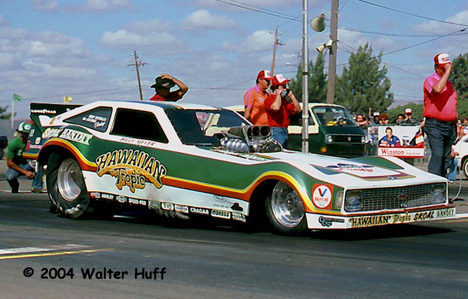

Billy Meyer is a little over two decades removed from the driver’s seat of a fuel Funny Car, yet his legacy remains as a driver,  drag strip innovator and one time, sanctioning body owner/president. That’s a pretty full resume for a guy from Waco, Texas.

drag strip innovator and one time, sanctioning body owner/president. That’s a pretty full resume for a guy from Waco, Texas.

Meyer believed he could achieve anything through the power of positive thinking and an insatiable desire to succeed, a credo he learned at the feet of his father, Paul, who made his fortune through the Success Motivation Institute (SMI).

As a drag racer, Billy was one of the best both in terms of driving and marketing. He was also, according to those who witnessed his racing career and competed against him, one of the wildest young men to have ever tried his hand at drag racing.

As a drag strip visionary, Meyer’s Texas Motorplex (located 35 miles south of the Dallas Metroplex in the small town of Ennis), with its all-concrete racing surface, would ultimately influence numerous super tracks that followed it, including Bruton Smith’s new facility in Concord, North Carolina.

His one failure nearly overshadowed the aforementioned triumphs. Twenty years later, the legend of Billy Meyer is making a comeback among drag racing fans who remember the yesterdays of drag racing.

From the time he burst onto the scene as teenaged Funny Car driver, (yes, that was his entry level ride) one could sense the kid was going to leave his mark on the sport. Meyer was the poster boy for the silver spoon set, living and acting the part. To suggest that he was confident in his abilities would be a significant understatement.

MEYER - THE EARLY YEARS

You can buy this full video at JACKSON BROTHERS VIDEO

a d v e r t i s e m e n t

Click to visit our sponsor's website

Some – make that “many” -- called Meyer cocky, but he resented this assessment. Once you understood his upbringing then you understood his demeanor. He was the son of Paul Meyer, founder of one of the country’s largest motivational institutes.

“I was raised to understand that you could do anything in life that you wanted to do, but persistence and determination had to be omnipotent,” Meyer says. “Obviously you have to be in God's will but if you set your mind to something there's really no reason that you can’t achieve a dream. Now obviously I was smart enough to realize I'm a 5'9", 140 pound guy, it doesn't matter how hard I wanted to play in the NFL or wanted to be on an NBA team, you have to work with those boundaries on what your God given talents are, but there’s no question that determination and persistence can get you a long way in life.”

Meyer had driven a nitro-burning Funny Car since 15, but acquired a competition license at 16. According to those from that era, he drove like someone on a mission, a mission clearly undefined. He was young and wanted to win. Such status defined many of his driving decisions.

Meyer never gave a second thought to the consequences of his actions when behind the wheel of a race car. Every time he fired his Funny Car, he did so with the intention of winning, and he did that numerous times in his driving career, regardless of the organization he was competing in.

A testament to his natural driving ability, Meyer drove his way to a semi-final finish at the IHRA Springnationals in Bristol, Tenn. during his 1972 debut. He also won the famed Orange County International Raceway 64-Funny Car Manufacturer’s Cup event that same year, this at a time when the OCIR event was more important to the Funny Car racers than was the IHRA national event in Bristol.

“I had just grown up being a very aggressive person,” Meyer admits. “I raced go karts, and you know the saying, ‘You don't know what you don't know.’

“You think you're fearless and that you can do anything, and that's the way I was raised. I never really thought about the consequences and what I was doing.”

Even the youthful exuberance in Meyer didn’t allow him to cross over into the realm of recklessness.

“I would probably say still to this day I'm one of the most cautious drivers ever and that sounds kinda funny but I didn't mind doing burnouts to the finish line at the Coca-Cola (Cavalcade of Stars) match races and those kinds of things,” Meyer says. “It didn’t matter what I did, whether it was spinning the car around if the reverser broke. I always had the parachute out early. I was always cautious.”

Yes, you read correctly. Meyer did have a tendency to spin his car around in his lane if the reverser broke. In fact, that stunt during the 1980 NHRA Springnationals in Columbus quickly drew the ire of then NHRA Competition Director Steve Gibbs, who watched on the starting line with a look combining disbelief and anger.

Meyer was able to spin around his car successfully but in doing so, crossed the centerline and drew a disqualification. This was not a real impressive sight. One had to wonder what Funny Car legend Raymond Beadle was thinking as he backed up and Meyer pulled in front of him following him back to the starting line in the same lane.

Once Beadle stopped on the starting line, Meyer simply pulled around the stopped Blue Max as if they were driving street cars in a parking lot.

“I never had an actual crash, never hit a guard wall in my life,” Meyer proclaims. “The first center line that I ever crossed was with the brand new Funny Car that we built that was just a little more aerodynamic design and didn't have enough down force on it and I crossed the center line during about the first 10 out of 15 runs. Other than that, I was an extremely cautious driver, but I was a very aggressive tuner. I guess that I had to be a cautious driver with the tune-ups that I had.”

The one accident that Meyer declines to speak of transpired in the 1970s during an IHRA event in Lakeland, Florida. His Funny Car ran off the end of the strip, hit a dirt berm and was launched into the air like a fighter off a carrier deck. It landed in a small lake off the end of the track. The accident almost ended Meyer’s life when he couldn’t extract himself from the car because the seat belts and shoulder harnesses wouldn’t release. Quick work by other racers saved Meyer to race again. The incident would ultimately result in the introduction of the quick release harness.

The accident resulted in a break from drag racing. Meyer later expanded his horizons over the years and later tried his hand at running for the land world speed record once, a feat that proved successful in the end.

THE INFAMOUS MEYER SPINOUT

a d v e r t i s e m e n t

Click to visit our sponsor's website

Meyer clearly had the resources to retain top-notch tuners, but for him, the challenge was being hands-on with every aspect of

the car, not just driving. In his 17-plus years of racing, Meyer served as his own crew chief and specialized in fuel system and clutch management.

“Nobody really knows that actually,” Meyer proclaims. “I had a lot of good crew guys; very talented crew members that worked for us. None of them were tuners, but they were talented people that could manufacture things. We did a lot of stuff in our own shop, but from the tuning aspect, from the clutch aspect, I would say in the 1980s Jim Duffy and Jack Deniker were very involved in the clutch tune up.

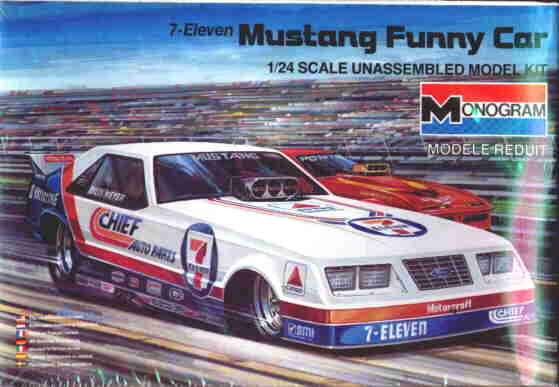

“The motor, unfortunately, was my responsibility and as I got busy with other companies, building the Motorplex and other projects that I had bought and stuff, I just couldn't devote enough time to do all of it, and with the responsibilities of 7-11 and Chief Auto Parts sponsorships.”

Prior to the time, he relinquished the role as a tuner, Meyer made the time to interact with the fans. He quickly gained a large fan following.

“I don't know if there’s anybody more down to earth than I am,” Meyer says. “I don't really know why the fans liked us. Obviously, we liked the entertainment portion of it. That's really what we were doing, except at national events. When we won the NHRA Winternationals with the first Skoal car, there wasn't a part left in our trailer at the end of that event. The first race of the year it was just kinda one of those things where if we had a problem we would do whatever we had to do.”

Certainly, a measure of those fans cheered on Meyer because he wouldn’t quit despite the overwhelming circumstances he faced.

“It's like at Indy when I blew that body off in 1986,” Meyer says. “I wasn't going to leave but I didn't have a Funny Car body, and I wasn't leaving until I figured out how to finish the event. We ended up making a deal with Kenny Bernstein for his spare, it took a day or two to mount it, but we ended up runner-up. I think people like that. People like to see someone that cares enough not to quit.”

He might not have held the stature of a gridiron giant, but his actions did at times.

“I did work a whole lot back then,” Meyer says. “I know without question at least two days a week I didn't go home from work. I would just roll the days through and I used to get sick a lot. I've had pneumonia seven times and it's all during the racing career. A lot of it is from that accident where I punctured a lung. I don't live that lifestyle anymore and I'm much more relaxed. I'm still very determined and persistent in everything that I do but as you get older you learn your body a little better.

MEYER: I WON THE RACE!

Drag racing was leaning more and more toward the corporate side that has engulfed today’s sport.

“I had to kinda make a decision and turn that responsibility over and in June of 1987, I turned that over to Dave Settles,” Meyer says. “That was just really the last six months of my racing that I drove and we won two races. The first race that we won I couldn't really say that he was the tuner there, but he was just watching and trying to learn our system and put in his expert opinion. We did win the NHRA Finals that year which was my last competitive event.”

Meyer once says he wanted to take drag racing to the next level following the completion of his driving career, but what he didn’t realize is he’d always taken steps towards that goal throughout his racing career.

Meyer is credited by some with being the first NHRA professional driver to utilize an eighteen-wheeler to transport his race operation from race to race, signaling drag racing’s beginning of the end for the use of a duallie and Chaparral-type enclosed trailer.

This kind of innovation coupled with Meyer’s confidence didn’t immediately make him a hero amongst his peers.

“I don't think I was liked very well by a percentage of them just because they thought that I had money and hadn't (paid) my dues or something, but one thing about life is that time will make you either earn respect or lose respect,” Meyer says.

Meyer admitted the first eighteen-wheeler was more out of necessity and safety than as a tool of showmanship. The larger rig also provided a better platform for Meyer to market himself to larger corporate sponsors.

“Everybody thought it was ridiculous, but obviously, it was a great billboard,” Meyer says. “It was one of the things that I had done that I continued to try to do forever to make the sport look bigger than it was at the time. It's hard to look like a big fancy sport when you're driving around in a pick-up truck. But, it was also a whole lot safer, speaking from the safety concept.

“Anything with air brakes and it's made to carry 80,000 pounds is a whole lot safer than a crew cab truck with a Chaparral trailer. We used to totally destroy a four-door, dual wheel crew cab in one year, when you drive 80,000 miles in it and it was worthless at the end of the year and it wasn't safe with electric brakes and things like that, carrying a trailer that weighed so much.

“Thirdly it was also less expensive than a Chaparral and a crew cab. I bought a used semi truck and I bought the trailer from Suzuki, it was their snow mobile race team trailer. It had generators in it and (was) already set up. All we did was to make changes to fit a Funny Car.”

Meyer’s larger transport rig was just one of the many marketing tools he kept at his disposal for attracting the larger companies into a sport still fighting for recognition and legitimacy. He was clearly on his way to elevating drag racing marketing to the next level.

“Ya know, people don't just go buy billboards to buy them,” Meyer explained. “People don't just slap names on race cars for their egos, and I think that's where a lot of people get confused. There usually has to be something else to go along to tie in to make that a win-win for everybody, whether it's a billboard at a race track or whether it's a race car. We did a lot of tie-in type stuff, we did a whole lot of different things, like we got companies into 7/11 stores when they weren't currently in the stores.”

Meyer used every ounce of marketing potential he could, ranging from his Funny Car sponsorships to his involvement with actor Burt Reynolds and Hal Needham on a land speed car.

“If you look at a lot of my sponsorship stuff, they’re in a lot of movies you'll watch (from that era), 'Cannonball Run', you'll see Don Deluise whip into a 7/11 to get coffee and say, 'Thank heaven for 7/11'. If you go see the street car race with Burt Reynolds in it you'll see that he's passing the Chief Auto Parts car and the Miller car.”

Many of those same principles are employed in running the Texas Motorplex.

“With a race track what we do is a whole lot of stuff for your helping companies get a relationship with the customer, whether it's the ability to sign up for sampling, whether it's getting people to recruit working for your company, there's just a lot of things that revolves in marketing and sponsorship that people just don't do,” Meyer added.

Meyer believed “back in the day” that he gained the larger sponsorship dollars when compared to many of his compatriots in the Funny Car world because of his personal marketing efforts. He believes many of today’s teams struggle with sponsorships simply because they approach things the wrong way.

“If you look at certain people that have sponsors for a long, long time you'll see that a lot of them are very astute people and they understand that it's not just technically putting a name on a car,” Meyer added.

a d v e r t i s e m e n t

Click to visit our sponsor's website

Meyer had built his name into the drag racing icons of his era through successful sponsorships, not to mention driving talent, which propelled him to 14 national event victories in NHRA competition and another 8 on the IHRA tour.

He’d done just about everything the racing community had to offer a Funny Car driver and just as young as Meyer was when he started competing, he retired from competition at a young age.

“I was 33-years-old when I retired,” Meyer says. “I just didn't want to be gone from my family. I wanted to raise my family. I had two children, one of them was born the week before Indy in 1982 and the other was born in 1984 after the last race of the year and I just didn't want to be a part-time parent. That was more important to me than the sport and I already had income from all my other business ventures. It just didn't make any sense to (race) anymore.”

Meyer had started a new chapter in his life as a family man, not to mention the demands of running the day-to-day operations of the IHRA, the major investment he made to replace the exhilaration driving had provided. We’ll go into that chapter of Meyer’s life in Part 2 of our story.

He still strolls down memory lane every once in a while and in doing so, Meyer finds it easy to remember those who helped him to achieve his good name as a drag racer.

“Grover Rogers helped me a lot in that earlier portion of my career and taught me a certain methodology of racing,” “Meyer says. “Then the Condit family and Gene Beaver, they took me under their wing when I was young and I used to live at the Condits' house, in the early winters in 1973 and 1974. We did a lot of things together, worked on cars together, we traveled. I would say that they were very, very instrumental in that portion of my career. We're still great friends to this date.

“Then I would say Steve Plueger was very instrumental and very supportive of my career and then as I moved on to different times. Sid Waterman was probably the most helpful as a mentor as a big brother-type of person that I could call any time and work with. I stayed with him for years. Gary Beck, I moved with him and stayed with him a lot.”

Meyer even remembers early in his career another aspiring Funny Car driver who just wanted to compete – John Force, now the only 1,000 round winner in professional drag racing history.

“We'd be working on the cars in the garage every day when I was over at the Condits, and he'd come over saying that he was gonna drive a Funny Car one day,” Meyer recalled. “We just kinda laughed at him at the time and obviously persistence and determination were a key factor in his life too.”

Meyer says he has no desire to return to drag racing either as a driver or team owner. He’s completely finished with that chapter of his life and a completely different person, too.

“I'm 54-years-old, raised a family and a lot closer to the Lord,” Meyer says. “Now when I do something in life and look back it doesn't look like Bosnia in the background. I've had ventures that weren't successful, just like the [purchasing of the] IHRA. If you haven't ever tried anything then you sure haven't failed but you haven't succeeded. Of course, every business venture that you try isn't always successful, but there are some that have worked greatly and when that happens, you feel extremely blessed. Whatever we do in life, is all sifted through God's hands and we live by grace and just try to do as much as we can in the time we have.”

PART 2 - COMING TOMORROW