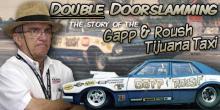

GAPP & ROUSH – HAILING THE CAB!

Throughout the fabled first five decades of the National Hot

Rod Association’s existence there have literally been hundreds of historical

moments and monumental “firsts.” As hard as it is to single out any particular

time frame or sequence of events that contributed the most to the NHRA of today,

arguably the years between 1965 and 1975 have to be considered among the most

significant. It was during that ten-year span that the mighty Super Stock

class, propelled along by heavy factory participation, spawned two new classes

which would go on to become mainstays in the professional eliminator category:

Funny Car and Pro Stock.

Throughout the fabled first five decades of the National Hot

Rod Association’s existence there have literally been hundreds of historical

moments and monumental “firsts.” As hard as it is to single out any particular

time frame or sequence of events that contributed the most to the NHRA of today,

arguably the years between 1965 and 1975 have to be considered among the most

significant. It was during that ten-year span that the mighty Super Stock

class, propelled along by heavy factory participation, spawned two new classes

which would go on to become mainstays in the professional eliminator category:

Funny Car and Pro Stock.

The evolution of the cars hitting the track in the early days of these fledgling classes progressed at an amazing rate, changing literally week by week as the creative minds of the day engineered, built, and raced machines of all conceivable configurations. This creativity often outpaced the rulebook, such as it was back then, leaving tech officials in a constant state of flux as they attempted to bring some semblance of stability to the new programs.

From Super Stock to Factory Experimental to Experimental Stock, Funny Car went on its weird and wonderful way, morphing wildly until at last emerging, somewhat under control, as a stand-alone class in 1969. Its more sedate, if not any less renegade, half-brother Pro Stock made it to the big stage one year later. Since we’re discussing one of Pro Stock’s most famous teams, and most famous cars here, we’ll leave Funny Car at this point to concentrate on the “factory hot rods.”

The Checkered History of Pro Stock’s Most Unique Factory Hot Rod

The evolution of the cars hitting the track in the early days of these fledgling classes progressed at an amazing rate, changing literally week by week as the creative minds of the day engineered, built, and raced machines of all conceivable configurations. This creativity often outpaced the rulebook, such as it was back then, leaving tech officials in a constant state of flux as they attempted to bring some semblance of stability to the new programs.

When the Pro Stock class struck out on its own just prior to the “Super Season” of 1970, it was for all practical purposes ruled by 426 Hemi-powered Chrysler cars. Based on that, the rules were fairly straightforward: 7 pounds per cubic-inch and a minimum weight of 2,700 pounds. Needless to say, things would not remain the same for very long, and where Pro Stock went from there is a fascinating tale; a tale perhaps best told by one of the people responsible for creating the car that best epitomized the free-wheeling early days of the class.

That man is

a d v e r t i s e m e n t

Click to visit our sponsor's website

“The club we started at Ford was supposed to be just a hobby thing, but it soon turned out that there weren’t enough hours in the day to do what we were doing on a hobby level – in other words, the member’s wives demanded more time than running a drag car required. It turns out that most of the guys weren’t really that interested – it just sounded great at the time – and when the pressure from the home front got too strong, they bailed out, leaving me on my own.

“Consequently, I ended up going into the racing business on my own while still an engineer at Ford,” Gapp said. “About that time the factories were heavily involved in the NHRA’s factory Super Stock wars. Ford had the Thunderbolt Fairlane, and Lincoln Mercury had the Comet, both lightweight cars with the single overhead cam 427 Ford engine. Because I was associated with the club, and because I had access to Ford engineering and parts, Lincoln Mercury ended up giving me one of their vehicles, because they couldn’t support the half-dozen that they had. Before the days of Pro Stock, the NHRA had cars like the Comet run in what was known as A/FX or Factory Experimental, and I held the class record for a period of time.”

An interesting side note to this story is the fact that

another of the factory Comets went to Jack Chrisman, and he created quite a

sensation when he brought it out at the 1964 U.S. Nationals as the sport’s first

blown, injected, nitro-burning Funny Car. The Comet was built basically as an

exhibition car, but it was really popular, and it was the first of what became

today’s fuel Funny Cars.

Gapp picked up the story once again. “At around this time,

there was an East Coast circuit that promoted so-called Gas Funny Car

competition, and I did that for three or four years as well. I was still racing

as a hobby back then, and had a lot of demand from other guys to build them

Ford engines, because there was no Ford expertise out there at the time. In the

late 1960s, I started a business building engines and doing other work for

racers. Business was good, and I soon had to move from my garage at home into a

larger, separate shop. This was just before Pro Stock became a regular

eliminator on the NHRA tour, and Ford, Chrysler, and Chevrolet were still heavily

involved. Cars basically ran 426 to 429 cubic-inch motors and to be legal a car

had to meet a requirement of seven pounds per cubic inch, with a 2,700-pound

minimum, I believe. Chrysler had the 426

Hemi, Chevrolet had the 427 and Ford guys ran either the 427 “cammer” or the

429. At Ford, I headed up the 429 program, in both its NASCAR and drag racing

configurations, so naturally I had first-hand knowledge of that engine, which

was very sophisticated for the time. There weren’t many people around who could

work on them or get parts for them, so between racing and building engines, I

kept pretty busy.

a d v e r t i s e m e n t

Click to visit our sponsor's website

“Within a year, however, Ford racing collapsed – we went to work one day and the doors were locked. They told us to go home until they called us. Later, they offered us all some menial jobs, which were a huge comedown after being involved in the exciting racing programs. I wasn’t interested in that at all, so trying to figure out what to do next, it came to me that if part of my job at Ford was helping guys like Don Nicholson and Hubert Platt with their drag racing programs, I could do what they were doing out on the track. I mean, I was supposed to be the guy who told them what to do, so why didn’t I do it myself.

“That was the official beginning of Gapp & Roush, which we brought out into the daylight in 1970, the same year that NHRA Pro Stock made its debut. Jack and I hit the track for the 1971 season with a 429-powered Ford Maverick because the NHRA was still running with the seven pounds per cubic inch rule in those days. Under those rules, Chrysler won every race, because their Hemi was a much better motor than the Chevy or Ford. It wasn’t long before Bill Jenkins was petitioning the NHRA to have the rules altered to allow the use of a small block engine in a Vega at the same seven pounds per cubic inch configuration. The NHRA bought into the idea, thinking that it was “six of one, a half-dozen of the other”, I guess. Problem was, if they had consulted their physics books they would have realized that it wasn’t all that straightforward. There was a thing called inertia, which no one took into consideration. Simply stated, if you take a 2,700-pound big-block car and a 2,300-pound small-block car and you let out the clutch on each one, it’s the inertia off the line that determines the performance during the first 60-feet of the pass, not the horsepower. In other words, if you kick a cement block and a block of wood, quess which one will travel the farthest? So, naturally, Jenkins’ little Vega just jumped off the starting line and consequently it killed the Chryslers during the 1972 season.”

Jenkins was onto something good, and Gapp didn’t waste any time in exploring the potential of a light, small-block powered short-wheelbase car. “During my days at Ford, I worked right beside the team that developed the potent 302 that was used in Trans Am racing – a motor that was later bumped up to become the 351 Cleveland. I had enough engineering skill and knowledge of the 351 to realize that by putting it in a little Ford Pinto we’d have an even better combination than Jenkins had with his Vega. The Pinto wasn’t as aerodynamic as the Vega, but the 351 was a superior engine to the Chevy small-block of the day, so it more than made up for the car’s boxy profile. Jack and I built a prototype Pinto to test the theory, which we blew up during its first test sessions. Ironically, a local guy by the name of Bob Glidden was at the track that weekend, and he asked if we’d be interested in selling the car. Looking back, we probably should have told him no, but we sold it to him just so he could came back later and beat up on us – a lot.

a d v e r t i s e m e n t

Click to visit our sponsor's website

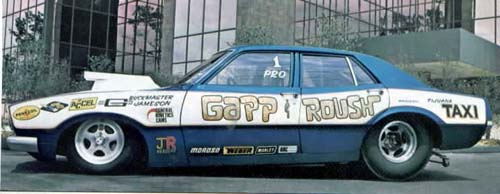

Gapp acquitted himself admirably in defense of his title in 1974, winning once and posting runner-up finishes four times with the team’s Pinto to close out the year in the No. 2 spot, just 168 points behind rival Glidden. After the ’74 season, however, the NHRA changed the rules again, giving yet more weight breaks to long wheelbase cars, dropping them down to 6.45 pounds per cube. “The way the new rules were written, cars just an inch longer than our Pinto, plus the Vega and the two-door Maverick, back to the longest of the Chrysler cars, got this break,” Gapp said. “Another rule which stated that cars used in Pro Stock could be no more than four years old was dropped at around the same time, and Guys like Glidden and Nicholson built ‘70 Mustangs to take advantage of the situation. It didn’t take Jack and I long to realize that the four-door Maverick, which was just slightly longer than the two-door, would fit into this category but still be shorter and lighter than the big cars. The real advantage was that we could turn an existing two-door car into a four-door in something like 60 days rather than starting from scratch with a Mustang.

“We knew of a guy who had a brand new two-door Maverick Pro Stock car built by Don Hardy, who built a very competitive chassis back then. We bought the car, removed the two-door body from the firewall back and lengthened the rear of the car to the factory spec. After acid-dipping it to reduce the weight even more, a four-door body was bolted to the frame. After we put the thing together someone said it looked like a Mexican taxicab, so the name “Tijuana Taxi” was given to the car, and it stuck. Back in those days, everyone was trying to find catchy names for their cars. Today, everything is a sponsor name, but back in those days, a car name was important.”

“We raced that car during the 1975 season, and had pretty

good success with it, too, winning three times and coming in runner-up three

times,” Gapp recalled with considerable understatement. Three wins and three

runner-ups in eight events is downright remarkable by today’s standards. Adding

to the legend of the “Taxi” was the fact that while it only saw competition for

one season, it was a very memorable one indeed. Glidden came into the last race

of the season second in the points chase behind Gapp. He appeared to have lost

the title in round one after red lighting against Paul Blevins' Vega, but he

got a reprieve and was reinstated when Blevins' entry came up light at the

scales. Gapp

could have clinched the championship by reaching the final, but a broken

connecting rod ended his bid in round two. With his main rival on the

sidelines, Glidden finished the job with a close 8.851 to 8.854 win over

Jenkins to take the title by 294 points.

a d v e r t i s e m e n t

Click to visit our sponsor's website

“It wasn’t just the rules that changed the face of Pro Stock over the years, though,” Gapp went on to say. “In the early ‘70s, if you were on top of your game, and had enough product sponsors, you could make racing a business. By product sponsors, I mean the oil companies and parts manufacturers who not only gave you products but paid you to run their decals on the car. But having said that, it was a hard fact that at that same time racing began to get very expensive. As an example, the chassis we had in the original Pinto that Bob Glidden bought cost us less than $3,000 in 1971. By 1975, that had gone to $12,000. Also in ’71, we used a standard $500.00 Ford four-speed “top loader” transmission with a little bit of re-work. The following year Lenco came out with the four-speed automatic, and those cost three grand – and you had to have a minimum of two of them. The cost of operating a race car at that time escalated exponentially - the numbers just skyrocketed.

“From the day I started racing in 1964, I had always approached it as a business. My cars always made a small profit. I kept records, watched what I spent and I operated in the black all the time. By the mid-1970s, though, big corporate sponsors were not yet involved to the extent they are now, and it became difficult to keep our heads above water. We worked very hard to entice major sponsors into the game – at one point Bill Jenkins even proposed that some of us team up and offer a Ford – Chevrolet - Chrysler package to any interested groups, because even with his name and record he couldn’t pin anything down on his own.

“Eventually, with no one beating down our door to throw

money at us, I decided that I wasn’t going to sit still and slowly go broke

playing with a race car. Around that same time I had been given the opportunity

to do prototype work for Ford, so we decided to hire Ken Dondero as a driver

for the car so that I could devote more time to working in the shop. That

really wasn’t the ideal situation, either, and with costs continuing to

escalate, Jack and I went our separate ways in 1978. He wanted to carry on in

the racing game and I wanted to pursue the prototype development work, so I

sold all my drag racing equipment that year and never looked back. I started

GAP Industries a short time later, and worked at that until I retired in 1986.”

So that’s the story of the infamous “Tijuana Taxi” and the

reason for its brief but never-to-be-forgotten existence. The famous Maverick

eventually ended up in

| {loadposition feedback} |