THE 'THOUSAND-FEET CLUB' IS ONE OF INDY'S ENDURING TRADITIONS

Very little of what once was Indianapolis Raceway Park remains. After fifty-five seasons, Lucas Oil Raceway is light years distant from the original dragstrip and road course which was designed to draw even more diverse motorsports to the city which was “the Home of the Five Hundred Mile Race.”

Even to those who attend only the NHRA’s U.S. Nationals each season, the track in tiny Clermont, Indiana, is constantly changing. The most recent addition, a huge new grandstand structure on the facility’s east side, filled a massive area which once stood vacant for all but the Labor Day weekend when wooden grandstands were rented for the event.

Previously, the Top Eliminator Club on the southwest corner of the property replaced a small angled grandstand and became a focal point of attention. More than thirty years ago, the construction of the massive Parks tower changed the face of the racetrack after the D-A Lubricants timing tower on the west side of the track was airlifted to duty at IRP’s adjacent two-thirds mile oval track.

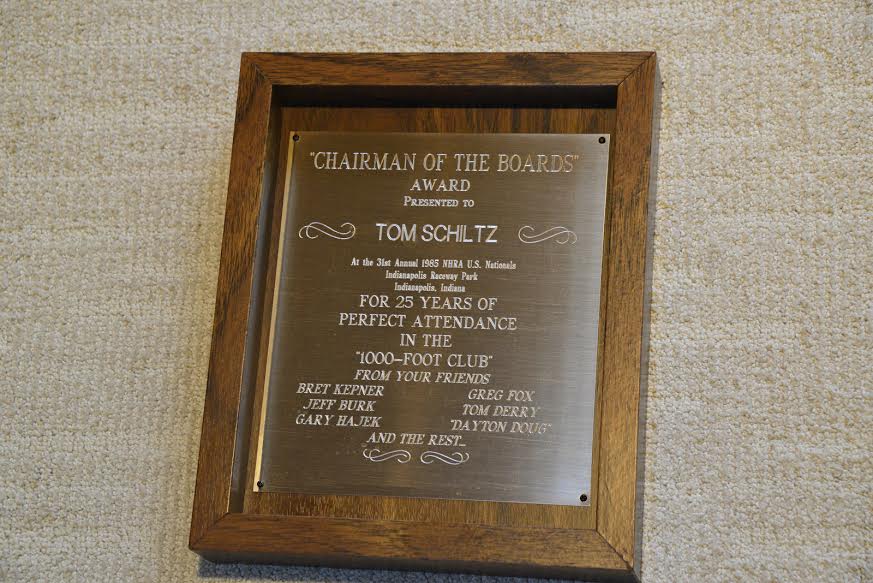

Since 1963, rudimentary grandstand seating, (ten rows high), was available from one hundred twenty feet downtrack of the starting line to one hundred twenty feet short of the finish line. It was on those wooden planks veteran photographer Tom Schiltz created the basis of what remains one of the tightest fraternities in drag racing.

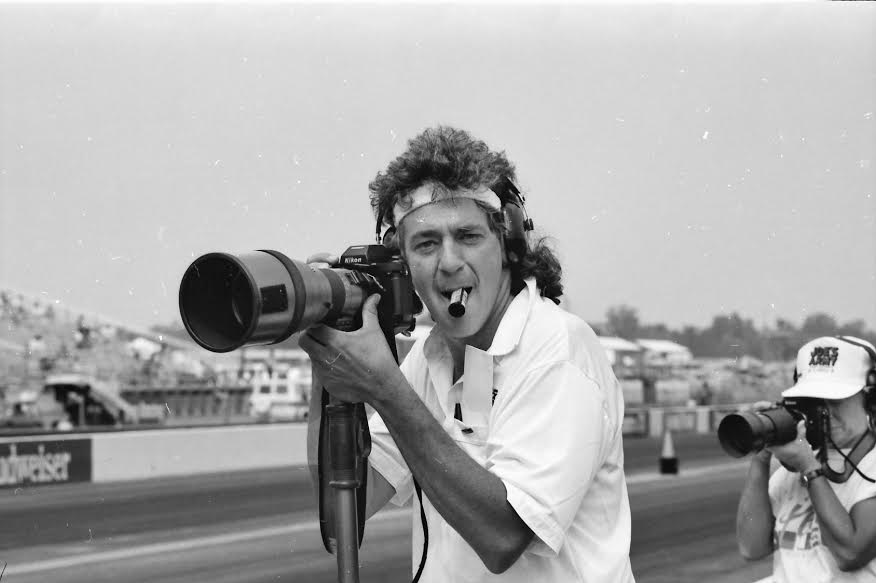

Attending what was then known only as “the Nationals” with fellow Ohioans Dave and Susie Koffel’s long line of Gassers, Schiltz made his home on the northern fringes of IRP from the first NHRA event in 1961. When the top-end grandstands were erected in 1963, Schiltz was one of the first to lay claim to the new viewing area. As Schiltz became a “paid professional” in drag racing photography, he often spent as much time shooting from those stands near the finish line as he did from the grass on the starting line.

At first, Schiltz camped at the three-quarter mark with his family. Later, it became a point of assembly for his friends. By the late 1960s, everybody knew to meet Tom in the top row of the west-side grandstands at “the thousand-feet mark”. This was long before a timing position was located one thousand feet from the starting line. At the time, it was an imaginary point somewhere roughly between half-track and the quarter-mile stripe. It was conveniently located only a few hundred feet south of IRP’s unique finish-line press tower which was often filled beyond its meager capacity with credentialed reporters covering the event for every known motorsports publication.

In the 1970s, (long before Electronic News Gathering techniques), only those “in the trenches” knew exactly what was happening at the six-day burndown known as “Indy.” Unfortunately, no single person could know everything which transpired in every class. A variety of journalists and photographers often gathered at Schiltz’s position if only to fraternize and discuss events transpiring during the drag racing’s longest week. Eventually, the press guys jokingly referred to the spot as their own special “club.”

“That’s really how it started,” recalled drag racing journalist and broadcaster Bret Kepner who, forty years later, still carries the banner, (literally and figuratively), of that group. “So many of those who worked with the hardcore magazines would hang out with Tom down there at the thousand-feet mark, it simply became known as the ‘Thousand-Feet Club’. However, it became the central collection point for the news of the race. Each writer from each publication had a specific class which was their focus of attention. None of us could know what was happening in every class and the media assistance back then consisted solely of handwritten qualifying sheets comprised of only driver names and performance numbers. When all those different reporters got together in one spot, they shared their information and everybody benefitted. It was, for all intents, drag racing’s first all-encompassing press room.”

“It’s important to remember one other aspect of drag racing back then,” cautions Kepner. “Until the 1984 season, there were no specific qualifying sessions. Racers from Top Fuel Eliminator to Stock Eliminator were competing every hour. Six pairs of Stockers were sent down the track followed by six pairs of Super Stockers, then six pairs of Modified Eliminator cars, then six pairs of Competition Eliminator machines, then four pairs of Pro Comp, four pairs of Fuel Motorcycles, four pairs of Pro Stockers, four pairs of Funny Cars and four pairs of Top Fuel Dragsters. The whole circuit took the staging director about forty-five minutes. After that, he would go back to Stock Eliminator and begin it again. That went on from 7:00 AM until dusk around twelve hours later.”

“When the reporters were in the pit area covering each category of competition,” Kepner said, “they were missing action on the track. The photographers, however, were shooting the action ontrack all day. The camera guys were the source of info for the runs the writers never saw. It was a very complex arrangement and everybody knew they were responsible for paying attention to what happened in front of them. The photographers knew who blew an engine but the writers knew the extent of the damage and whether or not the team could repair it.”

Soon, the more observant fans found out they could get all the details of the race simply by finding a seat in the general-admission area near the horde of “magazine folks” and many became annual attendees of what common slang eventually renamed the “Thousand Foot Club.” Kepner noted, “That really irritated the writers since they knew that name was a grammatical disaster but, as usual, ‘lazy’ won out.”

In the late 1970s, IRP became the first NHRA National Event facility to use scoreboards. This advancement was a godsend to the writers who now could compile their own results without relying on Indy’s oft-overdriven public address system. “Before scoreboards, both the media and the fans were totally reliant on the announcers for all performance information,” Kepner said. “The final qualifying results offered by the NHRA media directors included only each driver’s best performance for the entire event. If you wanted to compile results of every driver’s individual runs, you had to do it yourself. With scoreboards, it was actually possible to write those results by hand while sitting in the grandstands.

“Ironically, the race director sent cars at such a fast pace at Indy, it was almost impossible for one person to write down the elapsed times and speeds for each pair and then write down the names of the next pair. I and Kevin McKenna, (now a thirty-year veteran of NHRA Media), devised a system in which we would sit together and each of us would simply write the results from one lane. At the end of the day, we would copy, (by hand), the other’s ‘lane results’ and we would each have a complete record of the event. It was a phenomenal amount of work but it enabled us to have coverage detailed far beyond that of the writers who didn’t ‘work for it’. It’s how we kept our jobs.”

Through the 1980s, the “1000 Foot Club” developed a reputation among drivers, as well. It was not uncommon to find a variety of fuel racers and sportsman standouts sitting in ‘the Club” finding out what their competition was doing from the only real source of that information. “Chassis builders often came by to find out who was running best at different times of the day,” said Kepner. “Because we were so far downtrack, we had a much better overall view of the track conditions long before the NHRA started specifically preparing the racing surface for each class.”

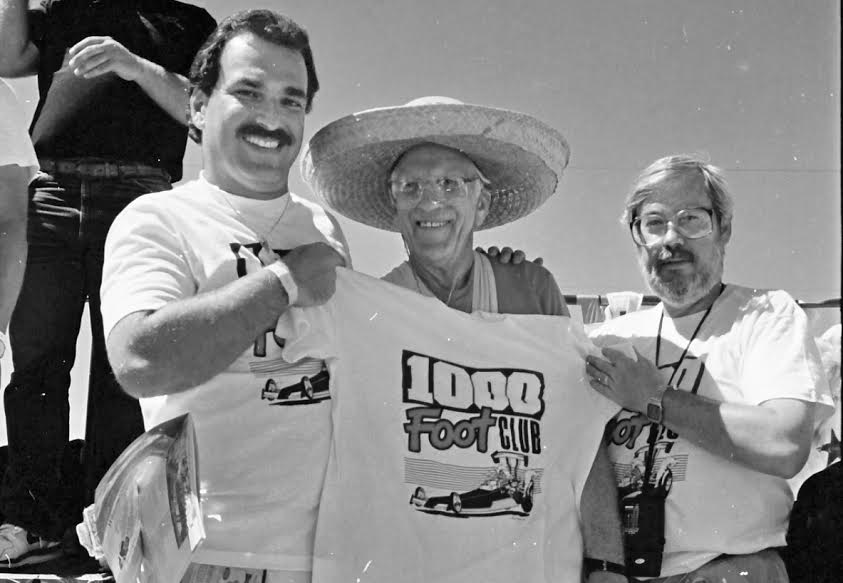

Meanwhile, the gathering of fans and media got larger. Using two mop handles and a bedsheet “borrowed” from Speedway’s American Inn, “the Club” had renowned artist Brando create the first “1000 Foot Club” banner which was hung from the top row of the west-side grandstands in 1981. Within a few years, new banners and even “1000-Foot Club” T-shirts were created by legendary artist Larry Williams. With the location now officially marked, the “Club" became even more popular. Eventually, professional drivers used the “Club” as the distribution point of everything from souvenirs to team apparel. The “1000-Foot Club” went mainstream but the top row was still the gathering spot for the media members outside of the air-conditioned, four-story Parks Tower which replaced the aging finish line press room in 1983.

In 1991, however, the “Club” was crushed by the mighty hand of progress. After the conclusion of the 1990 NHRA U.S. Nationals, the NHRA, (owner of the IRP complex since 1979), embarked on a five-year, two million-dollar expansion and restoration of the facility. The first thing to go was the entire west-side grandstand structure. In its place was a massive aluminum grandstand, thirty rows high, which included everything from seat backs to skyboxes. The four-acre renovation was christened the “Winston Concourse” in honor of the series sponsor and featured water fountains in the center of a huge walled courtyard where pavement included space for more than a dozen food vendors. The major problem was the fact the grandstands ended six hundred and eighty feet from the starting line.

Not only were there no longer any grandstands at the thousand feet mark, the entire second half of the track’s west side was to become “sponsor chalets” which would be rented for the princely sum of three thousand dollars for the Labor Day weekend, catering and open bar included. Incredibly, the viewing area would not even be elevated. The “Club” had no choice but to move to the top row of the new aluminum mountain.

The chalets were a failure and, within two seasons, the vacant lot where the “club” once lived became the compound at which the massive trucks for the event’s television coverage were parked. The original finish line press tower was eventually dismantled and the skyline of IRP took a decidedly modern turn.

Through the electronic revolution of the 1990s, information became much more accessible and the need for the fervent recording of information was no longer an issue. In the twenty-first century, results are now instantly in hand although the “Club” still remains a center for the discussion of each day’s events. More than a half-century after its founding, the “1000-Foot Club” is no longer packed from dawn until dusk; it’s only full when the professional qualifying sessions are scheduled. It is still the preferred seating area of the sportsman racers but they are now reduced in number to less than one hundred by Sunday evening.

Regardless, the top row in the far northwestern corner of the west-side grandstand at Lucas Oil Raceway is still occupied by a few dozen hearty, (and aging), souls who have spent the past forty Labor Days, (or more), within a group of hardcore media representatives and drag racing fans who comprise one of the last bastions of the sport’s early days.

Long live the “Thousand-Foot Club!”