GRIEF MANAGEMENT A TOPIC TODAY AS RACERS RECALL JOHNSON, TRETT 25 YEARS AFTER DREADFUL U.S. NATIONALS

Tom Weisenbach is Director of the International Council of Motorsport Sciences, a group of professionals dedicated to the scientific, medical, and educational aspects of the human element in motorsports. It explores the latest innovations and initiatives in motorsport safety.

Ironically, his first job in the industry brought him to Indianapolis Raceway Park (now Lucas Oil Raceway) 25 years ago. There and then, with the double deaths of Top Fuel driver Blaine Johnson and Top Fuel Motorcycle racer Elmer Trett at the 1996 U.S. Nationals, Weisenbach got a harsh introduction to the unforgiving and sobering side of racing.

The NHRA’s Johnson and Trett died barely 24 hours apart in violent crashes that occurred at almost the same spot on the racetrack.

“I couldn't tell you who won any of the classes but can tell you that we lost Blaine Johnson and Elmer Trett from accidents. None of us at the track spoke about what happened that weekend or afterwards. I went home Sunday night, knowing I had to go back on Monday for the finals but told my wife I couldn't believe we lost a driver and a rider that weekend,” Weisenbach said, reflecting on the horror that he witnessed a quarter-century ago.

“I often wondered how the Safety Safari members dealt with death and if there was any type of support offered to them. I was on the sales and marketing team. I can only imagine how the Safety Safari team felt that weekend when they got done. Back then, nobody talked about these incidents. There was no support. It was like, ‘Buckle up, Buttercup. Let’s go.’ I don’t know how the Safety Safari team got through that event,” he said, “because we continued on after they cleaned everything up.”

After Trett’s incident, Weisenbach said, “I went home and said, ‘What the hell? What just happened? What did I get myself into?’ I came from hockey, where you beat the hell out of each other but nobody got killed. Go into racing and you get two people killed in the same weekend.”

Those Left Behind that weekend simultaneously to soul-search and mourn included drag-racing legends Don “The Snake” Prudhomme, Kenny Bernstein, and Larry “Spiderman” McBride. Despite their years in drag racing and their appreciation for its powerful unpredictability, they, too, found themselves a bit lost and mightily moved.

Bernstein had been locked in a Top Fuel championship duel with Blaine Johnson. So seeing Johnson’s life snuffed out in a brilliant-turned-brutal flash was, in Bernstein’s words, “a terrible thing, the worst thing that could happen.” Johnson had just completed a track-record pass that gave him the No. 1 starting position, but such a feat, normally celebrated, became meaningless in seconds. His engine exploded in a fireball that is believed to have caused his rear tires to explode and wipe out the stabilizing rear wing. Out of control, his dragster hit one wall, then the other and plowed into an opening in the wall in the shutdown area. Nothing could save him.

Prudhomme went to the scene. “Normally I would do that if there was a big wreck or something. I think about safety issues and why this happened and why that happened. So there's nothing like going there and seeing for yourself. At the time, I didn't realize when he crashed that it had taken his life, that he had died,” he said.

At that time, Prudhomme was the team owner for driver Larry Dixon, and he said, Dixon “wanted to go down there [to the accident scene] and I said, ‘Don't, because he didn't make it.’ I didn't want Larry to see all that, the car and everything. It was tragic.”

Twenty-six years before that, in 1970, racer Jim Nicoll experienced a spectacular airborne wreck in the Top Fuel final round – opposite Prudhomme – that appeared un-survivable. Prudhomme, fearing the worst, vowed to quit the sport that put him on the map and vice versa. “I'm a pretty compassionate guy. The people don't know that. But I really care,” The Snake said. “When I thought Nicholl lost his life, I mean, I was really over it. I mean, it was dangerous.” And this smacked of déjà vu.

“That shook us all up. But the thing that blew me away,” Prudhomme said, “was that the next day, Alan Johnson [Blaine’s brother and crew chief] and the whole family, as far as I know, for sure, Alan Johnson was back at the racetrack, tuning on Jim Head’s car. I thought, ‘Man, this is some tough son of a bitch’. These people are really crazy about drag racing, or that's the way they show their grief or something, by just going back and keep going, I guess. From this day I thought, ‘I'm not quite sure how I would handle it.’

Bernstein handled it in a businesslike manner that masked his profound sense of sadness.

“You got two choices here: you go on or you quit,” he said. “When you put it on a piece of paper in your mind, this or this, it’s pretty easy to figure out which way you’re probably going to go.” And that’s what he conveyed to his team that next morning following Johnson’s passing.

“I got to thinking about it pretty hard there and I realized that we got to go on. We got to race today, and we got to take care of business,” Bernstein said. “When I got to the track the next day, my team was in the same boat I was in. They were absolutely down and just distraught and no energy. I guess all of us were thinking, ‘Did we really need to be there?’ It was just that bad. It affected all of us. The whole pits were that way. Everybody was that way.

“So I pulled my team together, and I said, ‘Let me tell you something that's going to happen: This race is going to go on. The season is going to continue. And someone's going to win a championship. I want you guys to think about that and how bad you want to have a chance to win. No, it won't be a win that we feel as good about, because we didn't get to race Blaine when he was leading the points. We didn't get to race him down to the wire and beat him that way, but we didn't make this thing happen. It's put in our laps, and we have a choice. My choice is to get up off the floor, go to work, and try to win this race and try to win a championship,’” he said.

“I felt real comfortable in talking to my team. We all loved each other,” Bernstein said. “But like I told him, I said, ‘somebody's going to win this thing when it’s all said and done. Life goes on and we got a chance now, the wrong way, but we got a chance to win this thing. Let’s just go do it. Let's finish it for Blaine. And we can win it for Blaine and take care of our business at the same time. And that's what we did.”

Bernstein won the 1996 championship and presented his trophy to the Johnson family at the year-end awards ceremony.

He sloughed off the notion that he had to become a counselor, as well: “Well, that's what they paid me the big money for.”

But Bernstein and wife Sheryl, distraught, went to the hospital to support the Johnson family.

“I didn't know him very well. We weren't best of buddies like [Joe] Amato and I were. But I had so much respect for him and for Alan and how they ran their cars and everything about it. I just told Sheryl, ‘We need to go to the hospital’. We stayed down there for quite a while, and it really affected me. I didn't know for sure then when we first got there, if he was gone. But soon someone came out a little later and told us. It just took all the wind out of your sails,” he said. “You just absolutely didn't know if you even wanted to go on. I found that very, in some ways, strange, because, again, I didn't know Blaine real well. I just knew him. He wasn't a close buddy or anything, but it was so much I felt about racing him, and I'm sure he felt that about us, too. I thought about it all night long, and I really was down.”

“I didn't know him very well. We weren't best of buddies like [Joe] Amato and I were. But I had so much respect for him and for Alan and how they ran their cars and everything about it. I just told Sheryl, ‘We need to go to the hospital’. We stayed down there for quite a while, and it really affected me. I didn't know for sure then when we first got there, if he was gone. But soon someone came out a little later and told us. It just took all the wind out of your sails,” he said. “You just absolutely didn't know if you even wanted to go on. I found that very, in some ways, strange, because, again, I didn't know Blaine real well. I just knew him. He wasn't a close buddy or anything, but it was so much I felt about racing him, and I'm sure he felt that about us, too. I thought about it all night long, and I really was down.”

Prudhomme grappled with similar feelings: “Blaine was at the peak of his driving, and he was an excellent driver. It was really an excellent team and to see that, to go down there and witness him getting killed, to see that and be there, and then to see them all of the track the next day. It just blew me away. I thought, ‘F---, this drag racing thing is like . . . These people are crazy’. I mean, aren't you going to take it easy for a little while or collect your thoughts? But they didn't. They went right back and went racing. It's like the old saying, ‘The show must go on.’ But this was personal. This wasn't just someone got killed in the class that you don't know. I thought, ‘Son of a bitch, what's it all mean?’

Dixon acknowledged that he had “definitely nothing as far as grief counseling. Myself, I've always depended on [chaplains] Larry Smiley and Craig Garland of Racers For Christ for guidance at the track.”

Prudhomme said, “Racers for Christ have always been a part of it. Some people needed the help, but some people didn’t. Everybody deals with it different. Alan Johnson dealt with it by going out to the track the next day and stayed busy. That's the way he dealt with it. I don't think I would have dealt with it like that. But you know, thank God, I never had to deal with that.”

And Bernstein said he received some counseling at the hospital.

“There was nothing official done in that way at all. I was talked to at the hospital by one of the Racers for Christ [representatives], because I was having a tough time with it. Again, I didn't know [Blaine Johnson] as well as I knew a lot of other people, but I sure had the world of respect for him and Alan. Anyway, I had a preacher talk to me there and give me some encouragement and kind of get me going back in the right direction. But there was nothing official going on at that time. I think my talk to my team at the time was as close to what I got.”

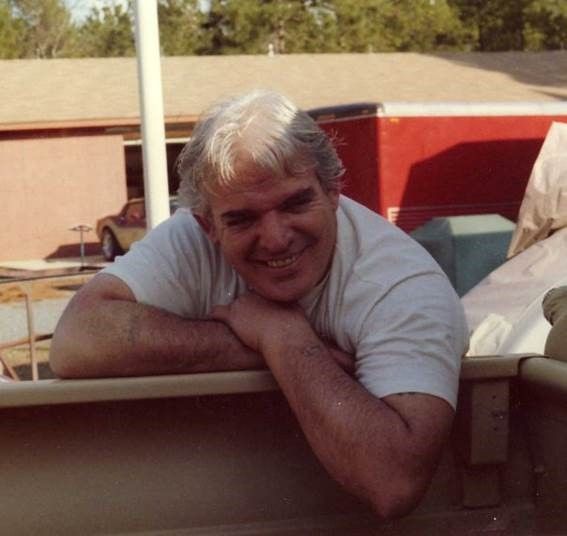

In the case of Trett, the same shock and grief jolted the motorcycle community, for Trett was to the bike world what “Big Daddy” Don Garlits was to “the nitro nation:” an innovator, pioneer, and icon.

But that day at Indianapolis, on drag racing’s grandest stage, Trett’s hand came off the bike and a gust of air lifted him off the seat and tossed him like a rag doll at more than 230 mph. He somersaulted violently across the path of competitor Tony Lang (who later would marry Trett’s daughter Gina) and into the sand trap. Trett died at the scene, leaving fans stunned and racers grieving and questioning their futures in the sport.

His one-time protégé McBride was one.

“I was just throwing-up-sick. I was in such disbelief, because he was the king, you know? How could this possibly happen? We didn’t even run the bikes after that,” McBride said. “I was so devastated that I couldn’t ride. I said, ‘I’m done. I’m quitting.’ His wife [Jackie Trett] came to me and said, ‘No, Larry. You can’t quit. You’ve got to keep going – you’ve got to keep this sport alive.’ I felt very honored and very flattered that she even felt that much of me to tell me that. It was a lot of pressure, because you couldn’t fill his shoes. There was one Elmer Trett and one only.

“And he was such a cool guy and so soft spoken. He was a big man, but he was so soft-spoken you had to listen when he spoke, because he didn’t speak very loud,” McBride said. “People had so much respect for him. He just had a thing about him when he came up to somebody it was automatically like he was the king. Just a lot of charisma is all I can say.”

He called Trett’s accident “an ugly deal, man” and said, “That morning, his blood pressure was low. We had breakfast together that morning. We had pancakes and stuff, and his blood pressure came right back up and he started feeling good. He still wasn’t feeling as good as he should have. It’s just my personal opinion only . . . I think when he shut the throttle off, all the G-forces, all the negative Gs, that he pulled, I think he got kind of blacked out. We’ll never know what happened exactly. But we do know that his right hand came off the handlebars and the wind got him and blew him off.”

McBride said Trett “was a great man. Elmer was one of my best friends. We think about him all the time. He was such a dear friend of mine. He did so much for me and my family. He was just a good man.”

Some positives have come from these incidents. Dixon said, “Because of how [Blaine Johnson] crashed, a lot of emphasis was placed on upgrading track safety. A committee was formed at the following race to raise standards [for] turnouts, guardrails, et c. Looking back, not much was done with cockpit safety or engine containment from crash.”

Prudhomme said, “The NHRA is doing a lot better job at it now. They still have that underlying problem at blowing the engines up. Fortunately, the cars are a lot safer than they were back then. There wasn't that much protection. I know when [Johnson] hit that guardrail, I don't think anything could have saved his life. But you just have a lot better chance in today's car. The guys and the gals that do this, I mean, the equipment that they're in is a lot safer. They're still blowing up cars, they're still blowing the engines, but they're able to walk away from them now.”

Still, racing in general has a way to go when it comes to mental-health counseling. However, medical experts such as Bjorn Vos, of The Netherlands, and others around the globe are leading the charge in this area of health and well-being.

Weisenbach said, “Safety has come so far since the ’90s that drivers and riders are safer now than ever, but racing is a dangerous sport and accidents happen. It is so important that sanctioning bodies and tracks provide support to their safety and medical teams. Mental health has been brought to the forefront for all of us as we have learned to manage COVID. It is OK to talk about what we are dealing with, at the track or away from the track.”

Be sure to follow us here for the latest used items for sale, and LIKE us on Facebook - https://t.co/Fg1S1NQDs2 pic.twitter.com/DGyEWcsyVN

— QuarterMileClassifieds (@QMileClassified) August 25, 2021