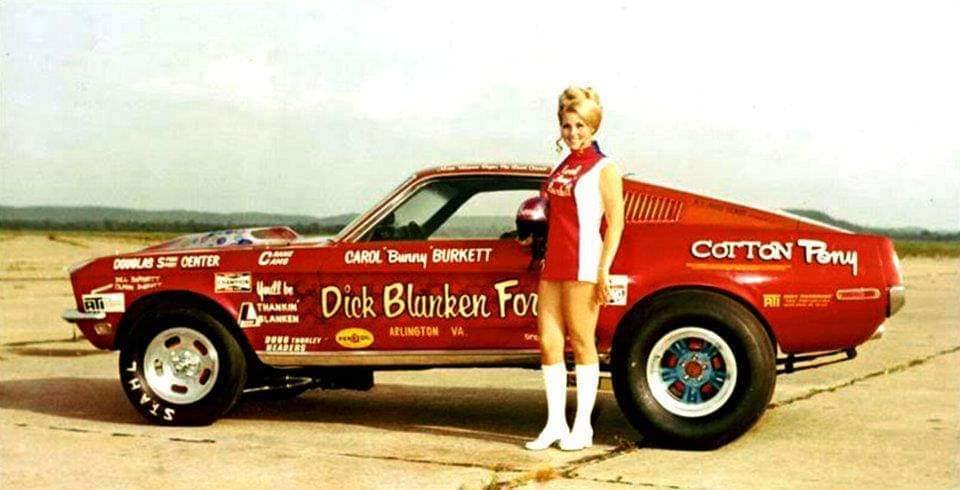

FRIENDS, FELLOW RACERS REMEMBER CAROL "BUNNY" BURKETT AS A ONE OF A KIND

Few have ever had, or will have, the long-term, positive impact on drag racing that Carol “Bunny” Burkett did in her half-century in the sport.

Few have ever had, or will have, the long-term, positive impact on drag racing that Carol “Bunny” Burkett did in her half-century in the sport.

Born on May 29, 1945, in Franklin, W.Va., the longtime resident of northern Virginia died in her sleep at home. Her family announced her passing on her Facebook page Saturday evening, and added that it “plans to have a celebration of life later this year when it is safe for all to attend.” It added, “... remember, Bunny NEVER followed the beaten path … she made her own.”

Nearly 1,000 people had left comments on that Facebook post within 20 hours, and scores of fans left their own posts on her page. Fans and fellow racers called her “icon” and “legend.” One devotee called her “the greatest woman to influence my life.” Others posted that news of Burkett’s death “shook me like a ton of bricks” and was “devastating.” Her website, bunnyburkett.com, was crashed by a multitude of visitors Sunday.

Her death “will leave a big hole in the sport and in the hearts of all who had the privilege of knowing her,” said Roberta (Schultz) Mack, who raced against Burkett dozens of times in the late 70s and early 1980s, and her husband Tod Mack, a former owner of Maryland International Raceway.

Burkett raced in big media markets as well as hole-in-the-wall rural tracks. She captured the 1986 IHRA Alcohol Funny Car championship on the strength of victories at Darlington, S.C., Martin, Mich., and Rockingham, N.C. She was an NHRA divisional champion, and she scored her only NHRA national-event win that same year, beating Peter Gallen in the finals of the Keystone Nationals at Maple Grove Raceway.

Oddly, though, the on-track accomplishments take a back seat to the mark she left on fans, the media, and other racers such as Arnie Karp, Todd Paton and Scott Palmer, who left their condolences on Facebook.

Oddly, though, the on-track accomplishments take a back seat to the mark she left on fans, the media, and other racers such as Arnie Karp, Todd Paton and Scott Palmer, who left their condolences on Facebook.

Said Aaron Polburn, the president of IHRA from 2004-14, “She was a drag racing entertainer before we, as promoters, knew we were in the entertainment business.”

That was the truth.

Born Carolyn Ruth Hartman, she married Maurice “Mo” Burkett, a local hot rodder in northern Virginia, when she was 16. He initially dismissed her desire to race cars but quickly discovered she could not be more serious about her wishes, and he bought her a 1964½ Mustang. That car was destroyed by a drunk driver, and its replacement became her race vehicle.

She began competing with a circuit of female drivers called the Miss America of Drag Racing, which later changed its name to Miss Universe of Drag Racing. By 1973, she had stepped up to the Pro Stock ranks with a Ford Pinto -- a car she dubbed “Cotton Pony” -- and three years later, climbed aboard an alcohol-burning Funny Car. She had worked a very short stint as a hostess at the Playboy Club in Baltimore, Md., but she parlayed that brief experience into the nickname that became a moneymaker to help support her racing efforts.

“Bunny” Burkett booked a steady stream of match races against men and women from the northern end of the East Coast down through the Carolinas. Sales of merchandise helped fund her team, and she proved to be the consummate salesman in building a legion of fans/customers wherever she appeared. While others spent their time and money chasing championships with sanctioning bodies, she kept her team going by racing at tracks in remote areas.

“Bunny” Burkett booked a steady stream of match races against men and women from the northern end of the East Coast down through the Carolinas. Sales of merchandise helped fund her team, and she proved to be the consummate salesman in building a legion of fans/customers wherever she appeared. While others spent their time and money chasing championships with sanctioning bodies, she kept her team going by racing at tracks in remote areas.

“When she moved into Funny Car, that’s when it stopped mattering if she won or not because you had a woman in a Funny Car, and that was huge,” said veteran announcer and historian Bret Kepner. “It was a huge deal, mainly because of the places she booked. If she ran at Maple Grove, it wasn’t going to be front-page news the next morning in the Philadelphia Inquirer.

“But if she ran at Ware Shoals, South Carolina, it was a big deal. … All those little tracks she raced at in the 70s, she was like the Second Coming. I mean, what more could you ask for? A female in a Funny Car who was attractive and had been a Playboy bunny -- that’s worth $5 to go see …”

She eventually connected with Bill Matheis, who sponsored the pink Matheis & Burkett car starting in 1985. The following season, with Bill Barrett making the tuning calls on a new Chrysler Laser-bodied entry, Burkett reached the zenith of her career. She won the IHRA season opener at Darlington, and ensuing victories at Martin and Rockingham cemented her title. At Martin, she downed Gallen, then topped him again at the NHRA’s national event in Pennsylvania en route to a fourth-place points finish for the season.

“She had molded this whole persona of the demure, kind of shy, ‘I’m just a girl from down the street,’ ” Kepner said. “But deep down inside of her, there was a competitive drag racer. … There’s no question that in 1985-86, she was an absolute killer. She outran people and was running big numbers. She was a genuine ‘hitter’ for the first time in her career.”

She also became a top-shelf cheerleader for IHRA during those years, said Ted Jones, a former president of the sanctioning body.

“She was really good with the media, so we would take her on press tours before national events,” Jones said. “She was very outgoing, very friendly, and a good-looking gal and could get a lot of coverage. She would always take her time with the fans for a picture or autographs, and she was very competitive. She was very good for the sport.”

“She was really good with the media, so we would take her on press tours before national events,” Jones said. “She was very outgoing, very friendly, and a good-looking gal and could get a lot of coverage. She would always take her time with the fans for a picture or autographs, and she was very competitive. She was very good for the sport.”

In 1987, she reached the finals at an IHRA race at Atco, N.J., where she was the runner-up to Karp and his “Boston Strangler” entry.

A year later, she made an impact off the track when CompetitionPlus.com publisher Bobby Bennett was struggling to get his fledgling new printed magazine up to speed. Burkett “stepped up and purchased an ad from me,” he said, “and always encouraged me along the way. The sport, and this world, has lost an absolutely wonderful human being. My heart is broken.”

She scored her final national-event victory in 1991, toppling Mark Thomas in the finals of the IHRA’s kickoff event at Darlington. That was an impressive feat, given that Thomas would win seven IHRA Alcohol Funny Car titles and 23 national events.

At the time Thomas began his Funny Car career around 1984, he knew of Burkett only from photos and magazine articles. Then he was hired to compete against her in a match race in Cayuga, Ontario, and discovered she was “so nice, she was attractive, so personable, and she knew how to treat the fans and everyone. That was a blessing that more people should learn.

“Some people are nice to the cameras and nice to certain people,” said Thomas, who retired a decade ago to focus on his family and their 2,000-acre farm in Ohio. “But Bunny was a nice person, and that paid incredible dividends. How could you not like her? She made such a big impression on me by the way she dealt with people, and I tried to emulate that.”

On Sept. 4, 1995, Burkett’s life and career suffered a devastating blow. As she and Carl Ruth neared the finish line at Beaver Springs (Pa.) Dragway, Ruth drifted into Burkett’s lane, clipped her car and sent it careening off the track and into trees. Rescue crews needed 25 minutes to extract her from the wreckage, and she spent three weeks in a coma at a local hospital with two broken vertebrae, a broken wrist and ankle, and a hairline skull fracture.

When she returned to action more than a year later and with a noticeable limp, she did her best to pick up her career where it had been interrupted. At one of her first races back, at Maryland International Raceway, Thomas watched her get into the head of her first two opponents by telling them she wanted to go first in the burnout process. She then got the jump on both drivers when the green light flashed and beat them despite a slower elapsed time. Thomas said he made up his mind she wouldn’t go 3-for-3 using that tactic.

“She came up to me and (crew chief) Rick Hickman and said, ‘Let me start the car and do my burnout first, my poor ol’ body doesn’t work right.’ This is nothing against her, but I saw her getting in people’s heads two rounds in a row,” Thomas said. “So I get in the car, get strapped in, and Rick says, ‘I’m going to let her do her burnout first.’ I said, ‘Listen to me, we’re racing for a championship. When they say start the cars, you start the car, put the body down and get the hell outta the way.’ “So, Bunny’s rolling up to the water. I passed her and did a burnout before she could, so now she’s gotta play by my rules, OK? Nothing against her -- nothing against her -- but I saw her get in those guys’ heads. She wanted to win and so did I … and we beat her.

“We got to the other end and she said, ‘What part didn’t you understand that I wanted to do the burnout first?’ Some reporter was standing there and asked me, ‘What’s it like to beat Bunny on her comeback tour?’ I said the same thing to him that I said to her, ‘I don’t care if it’s Mother Teresa in the other lane, when you put on a firesuit and the engine starts up, it’s drag racing.’ She was a true competitor.”

In the aftermath of her crash, Burkett wasn’t shy about sharing the religious faith that helped her through the ordeal of recovery. She began displaying a Racers for Christ decal on her racecars, and she became an active supporter of Godspeed Ministries.

In the aftermath of her crash, Burkett wasn’t shy about sharing the religious faith that helped her through the ordeal of recovery. She began displaying a Racers for Christ decal on her racecars, and she became an active supporter of Godspeed Ministries.

“She loved sharing her faith,” said Godspeed co-founder Renee Bingham, who worked in the control tower at IHRA races for well over a decade. “We had great conversations of what God has done in our lives. One way she demonstrated God to others was always having time for them. She made you feel special by stopping what she was doing to talk to you. God always has time for us. Bunny knew that. She shared that. She touched many lives.”

Burkett is a permanent part of the scenery at Maryland International Raceway, which was her de facto home track and a place she raced at countless times. Royce Miller, who owned the track for 25 years and has managed it the past five after selling, recalled telling Burkett his plans to build a diner on the property, adding that he wanted to mount a car on the roof. She offered him the body from her championship car, a chassis on which to mount it, and enough parts to construct a mock engine to complete the look.

“She’d been at the track every year it’s been under my watch,” Miller said. “What separated her was her ability to market herself to the fans. I don’t know of anybody that spent more time with the fans. She would stay there until the very last person who wanted an autograph or picture or to say hello had their chance. I mean, every single race she’d be at the rear of her trailer, and she never left until everyone had a chance to interact with her.”

In addition to dealing with the long-term effects of her crash, Burkett also battled breast cancer. And while she had made occasional treks to the dragstrip in recent years -- Jones said he last spoke to her at a Super Chevy Show at Virginia Motorsports Park “a couple of years ago” -- Thomas said he had noticed a marked decrease in Burkett’s Facebook updates in recent months. Even so, to learn of her passing from Kepner’s post Saturday left him with a definite sense of loss. “

We weren’t expecting it, and for a lot of ‘us racers,’ she was our first hero,” he said. “I responded to the post about her passing with ‘Rest in peace, Bunny.’ But it didn’t feel right to type that. I’ve said that before when people died, but I think that’s the first time I’ve typed it that it just didn’t feel right.

“I can’t believe she’s gone. She touched a lot of people. She always had time for everybody. Everybody. If anybody learned anything from her, that ought to be it.”