CRAIG SULLIVAN HAS MASTERED THE ART OF VERSATILITY

A forgetful person might slip up if they’ve driven as many types of cars that Craig Sullivan has in recent years.

A forgetful person might slip up if they’ve driven as many types of cars that Craig Sullivan has in recent years.

He’s raced in three categories, all with different types of power adders to boost the horsepower potential of each vehicle’s engine.

Hopping from one seat to another isn’t as simple as it might seem. After all, a car’s a car, right? But each power adder Sullivan has used has unique characteristics that require razor-sharp focus. There was a learning curve for each, just as was the case for other drivers who have tried all three boosters, including Pro Modified standout Todd Tutterow and former PDRA Pro Boost world champ Kevin Rivenbark.

There are different G-forces in play on the driver depending on which power adder is employed, both at the launch and once the chutes are deployed. There are different techniques for pre-staging and staging the cars -- and on and on.

“The nitrous is very similar to a blower car as far as the staging,” Sullivan said. He added that he was initially unable to ‘bump’ the Mark Woodruff-owned turbocharged Vette into the staging beams in testing until he was told to “floor the gas pedal.”

Sullivan is a 55-year-old business owner from Avon, Ind., who’s been racing since he was 16. He has a racing lineage, as his father raced Modified Production in the 1970s, and Craig has “lived on the west side of Indianapolis all my life, so we were literally six to eight miles” from what is now Lucas Oil Raceway, home of the NHRA’s premier event, the U.S. Nationals.

For the past 27 years, he’s owned and operated Sullivan’s Equipment, which provides the machinery to run body shops. It sells Car-O-Liner equipment and other lines that provide racks, computerized measuring and welding, and more.

“We install it, we train shop employees on it, we service it. We’re a one-stop shop, so the customer has only one person to deal with,” he said. His 11-person staff covers Indiana, Kentucky and Tennessee, and it includes Super Stock/Stock/Super Street racer Ronnie Maggart.

The company’s success helps fund Sullivan’s passion for speed.

His racing experience with nitrous came in the Top Dragster ranks. He competed in a very popular, extremely competitive bracket program for NHRA Div. 3 racers, the Jeg’s Super Quick, in which cars can’t cover the eighth-mile distance in under 4.5 seconds. It was common, he said, for a 32-car field to be separated by no more than 6/100ths of a second at tracks such as Bunker Hill (Ind.) Dragstrip, Kil-Kare Dragstrip in Xenia, Ohio, Coles County Dragway in Charleston, Ill., and Crossroads Dragway in Terre Haute, Ind.

“I had a good 15 years experience with nitrous, and there was a time where my big-block, Ford-powered dragster was the fastest Top Dragster car in the country,” Sullivan said. “The fastest we’d ever been at that point in time (in the quarter-mile) was 6.09 at 221 miles an hour with a 706-inch billet Ford deal with Induction Solutions nitrous on it. Now that I haven’t raced Top Dragster in six years, it’s nowhere to where these guys are at now.”

A little less than six years ago, Sullivan decided to step up to the Pro Modified ranks, which meant a shift from nitrous oxide as the power adder to a supercharger; first a Roots-type piece prior to a shift to a DMPE screw-type weapon. He said the reason for abandoning his known-quantity nitrous in Top Dragster for something foreign to him in Pro Mod wasn’t a tough decision.

“Nitrous in Pro Mod is rocket scientist-type stuff, not like Top Sportsman or Top Dragster,” Sullivan said. “You’re looking at a 959-inch motor -- some of these guys are over 1,000 -- so now you’ve got to figure how to keep this motor running and put nitrous to it. There’s not but a handful of people who do that.

“Nitrous in Pro Mod is rocket scientist-type stuff, not like Top Sportsman or Top Dragster,” Sullivan said. “You’re looking at a 959-inch motor -- some of these guys are over 1,000 -- so now you’ve got to figure how to keep this motor running and put nitrous to it. There’s not but a handful of people who do that.

“The blower side was far more attractive because I knew of Darren Mayer (the namesake behind DMPE), and we talked about a lot of stuff when I was looking at putting this program together. Turbo was too much to learn.”

That last power adder changeover was alleviated when he got the offer to drive Woodruff’s turbo Vette. It’s tuned by Joe Oplowski, who is involved with Bob Rahaim’s NHRA Pro Mod entry, and Mark Menser of Menser Motorsports, a shock expert..

Here’s a look at the traits that’re similar and different with each power adder.

When it comes to nitrous oxide, the gas with which he has the most experience, Sullivan said that life ‘on the bottle’ is “very similar” to a supercharger in the way in which he stages the car for a run. The turbo’s nothing like either of those. More on that aspect in a bit.

What’s different with nitrous, Sullivan said, is that “you really need to look at bottle pressure. You’re able to tune each cylinder, which is good, and the staging process is very similar to staging a blown car.”

Staging the turbo Pro 275 Vette for Woodruff, who also owns and drives a turbo Camaro that he wrecked at Darlington, S.C., earlier in the year, is a completely different matter, Sullivan said.

“There are a lot of these turbo guys that don’t really look at the advantage you’ve got up front on the starting line when you can go double-oh-something in a blown car or a nitrous car and you can only go .085 in a turbo car because it really won’t move that first 6 inches,” Sullivan said. “You’ve really got to try to look at that turbo product and go, ‘This is not about the 60-foot, it’s about the first 6 inches.’ It really doesn’t matter how fast the 60 is. The first 60 feet plays into it, but the biggest percentage is how much the car moves in 6 inches. There are some guys catching on with it. When we set the record at Orlando for Pro 275 at 211.33, I think the margin of victory was 19/10,000ths that Joe Thompson beat me by.

“The blower car and the nitrous car, you basically roll into the beams, you roll in and turn the final stage light on, and you’re ready to go. With the turbo car, you do your burnout, you back up, you’ve got to arm your boost controller and the RacePak, and then you’re going to take a roll in. You roll into the pre-stage like you would in any car, but now you’ve got to bump the car in. You’ve got to really match brake pressure to converter charge. …

“You look at the high-end turbo cars, there are guys that take and hit their bump button and it rolls in real slow and they control it that way, and there are guys like me that sit there and bump it to count that 7 inches to get in the beams where we want to be. That’s really the technical side of it.”

Once the green flashes, then the differences become more obvious -- to the driver, anyway, Sullivan said. The biggest of the eye-openers comes with a turbocharged blast.

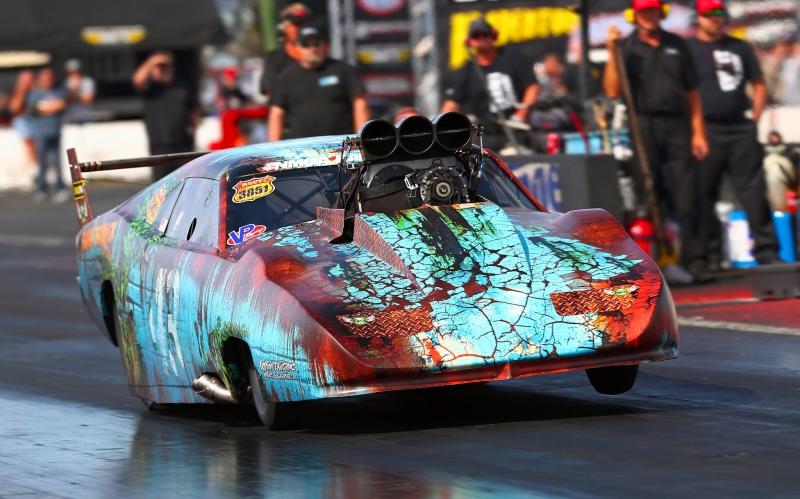

“My blown car, it never matches the G-meter out there like the turbo car,” he said, referring to his Pro Mod Dodge Daytona called “Barn Burner” for its unique graphic design. “The turbo, it’s like a never-ending … it’s just, like, unlimited thrust. It’s like you’re in a jet and when you take off you feel the Gs, but when the jet gets airborne, just off the ground, that’s probably the biggest Gs at about 2.

“The turbo, when it really starts running, it’s 3.3 to 3.4 Gs, or almost 3½ times your body weight. It will carry that from about 150 feet out to the 660 (or finish line in eighth-mile racing). In every other type of power adder, the G meter is falling off, and you can feel that the weight’s not on you as much anymore. But in a turbo car, you’ve got all these Gs on you, and you’ve got almost twice the Gs negatively” during deceleration when the parachutes pop open.

“The turbo, when it really starts running, it’s 3.3 to 3.4 Gs, or almost 3½ times your body weight. It will carry that from about 150 feet out to the 660 (or finish line in eighth-mile racing). In every other type of power adder, the G meter is falling off, and you can feel that the weight’s not on you as much anymore. But in a turbo car, you’ve got all these Gs on you, and you’ve got almost twice the Gs negatively” during deceleration when the parachutes pop open.

The Pro Mod Daytona was once campaigned by North Carolina’s Chip King. With Sullivan behind the wheel, it’s uncorked a best of 3.72 seconds at 208 mph last year at Indianapolis with air properties offering the equivalent to racing at 3,000 feet above sea level.

“The blower car, I just got in and let go of the button. Nobody really showed me what to do, and it drives very similar to the nitrous car so I wasn’t worried about it,” he said.

“But going from the dragster to that fast of a door car is a big change, especially the Pro Mod application because there’s no visibility,” he said of being behind the engine instead of in front of it, as he was in the dragster. “If I’m in the left lane, I’m looking through the throttle linkage through the butterfly on the right side of the blower to see the tree. If I’m in the right lane, I’m looking through the door window where the safety glass is to see the tree. That took a lot of getting used to.

“We bought the Daytona as a rolling car,” he added. “It was a used car, extremely used. It’s hard to say there’s a used Pro Mod that was only driven on Sundays by Granny. This is a 2006 car, and the average car I race against in NMCA and Mid West Pro Mod is a 2015-16, so my car is that much older.

“We had Vanishing Point (Race Cars) do some work for us in the beginning. I’ve become real good friends with Larry Jeffers, and he’s updated it two or three times for me. We’ve got a very competitive car now, but it’s just heavy, so he’s building us a new one.”

When asked why he changed from an initial Roots-type blower set-up to to a screw-type supercharger, Sullivan said it boiled down to his friendship with Mayer and a rules change that left him at a big disadvantage.

“He’s got about 80 percent market share in Top Fuel and Funny Car with the blower business. The engine’s a Brad Anderson-based Hemi with TA-1 heads that has DMPE’s intake and exhaust port on it, and we maintain it at my engine shop, Wild Irish Racing Engines. The rules started out at 2,500 pounds for a Roots car and we weighed 2,550. I thought we could find enough power to overcome the 50 pounds, then the rule changed to 2,450 -- so we dropped the Roots and went to the screw rotor.”

When he got the chance to tackle Woodruff’s Pro 275 turbo Vette this year, everything was new -- just as it had been when he made the shift from Top Dragster to Pro Mod, when he caught some heat for struggles out of the box with the Daytona.

“That’s the funny thing, because all my bracket racing buddies are going, ‘Why aren’t you doing better?’ ” Sullivan said. “In Top Dragster, it’s a case of ‘you need this low gear and you need to order this, this and this from Marco Abruzzi and you’ve got a bulletproof transmission,’ and you’re all set.

“In Pro Mod, everyone’s got a 521 or 526 Hemi, but there might be a thousand horsepower difference between them and you just don’t know. We floundered around the first full year and finished sixth in NMCA points. We hadn’t won a race in the six years we’ve been running ‘til Tulsa” in early May. At that event, which was part of the Mid West Pro Mod Racing Series, Sullivan lost in the first round of eliminations, then rallied to win the Slammers part of the show in which the first-round victims can “buy back” into a separate competition and are pitted against each other.

“We had an extremely competitive car. The driver screwed up first round. We qualified fourth in a 16-car field and got beat on the tree, which is bad when that’s what you’re known for,” he said with a laugh.

Sullivan depends heavily on car chief Tommy Radloff to keep the “Barn Burner” ready to hit the track, and more.

Sullivan depends heavily on car chief Tommy Radloff to keep the “Barn Burner” ready to hit the track, and more.

“He maintains the car 100 percent, plus the trailer and the coach, and he also runs my engine shop,” Sullivan added. “We do a lot of small-tire stuff. We just delivered a 785-inch nitrous motor to a guy in Michigan; had a 500-inch small block for a guy in Kentucky three or four weeks ago; got a boat customer with a Ford engine; a big-block Chevrolet deal with ProChargers on it; coupla tractors.”

When it was time to team with Woodruff in the turbo ranks, they headed to Bradenton, Fla., for some 2020 preseason testing and, as it turned out, a quick dose of basic driver’s ed.

“Mark was standing beside me while I staged, and I rolled up, turned the top bulb on. I went to go bump in and it wouldn’t bump in, so I shut the car off and opened the door,” he said. “He asked what was wrong, I said, ‘It won’t bump in.’ He said, ‘Put the accelerator all the way down.’ So I shut the door, started it, revved it up, put it to the mat, bumped it in, let go of the button and it went down the track.

“It was one of those deals where learning the operating procedure is crucial, but Woody’s a pretty good trainer and doesn’t get upset very easily. He and I have known each other a long time, used to be competitors, and now we’re peers. We probably talk to each other two or three times a day whether it’s business, racing or something else.”

It’s all part of the learning curve when you’re switching from one power adder to another. And with races that last less than four seconds, you’d better be a quick learner.

For 20 years, https://t.co/Reh86n8GFm has kept you covered when it comes to drag racing news. Thanks to the team at https://t.co/RJQ6L0BTUR, we can keep you covered when face coverings are necessary. We are offering custom face masks for $10. TO PURCHASE - https://t.co/Us0V173xw0 pic.twitter.com/DGRo368LDw

— Competition Plus (@competitionplus) July 16, 2020