THE TOD MACK MEMOIRS: NASCAR PT. 2, REMEMBERING THE EXPERIENCE

Tod Mack, a former owner of Maryland international Dragway, had his fingerprint on many promotions and innovations from the heralded facility located in Budds Creek, Md.

Tod Mack, a former owner of Maryland international Dragway, had his fingerprint on many promotions and innovations from the heralded facility located in Budds Creek, Md.

Mack, whose promotional home runs included the US Pro Stock Open, Mountain Motor Nationals, and The Wild Bunch, solidified his name in the ranks of significant drag racing contributors.

Mack was the first to use a pairings ladder based on qualifying times for the nitro cars when he ran the NASCAR Drag Race Division in the 1960s. Tod and Larry, along with Lex Dudas and Mike Lewis, created the ET Bracket Finals program in the early 1970s, which the group finally turned over to NHRA after a few years. MIR was the winner of the Inaugural event held at York US 30 Dragway. All in all, Tod Mack owned or operated six tracks over his career, and MIR fans benefited from his decades of experience.

In addition to the more successful promotions, Mack and longtime partner Larry Clayton introduced the world to the first four-wide fuel Funny Car match (almost four decades before Bruton Smith did the same thing in Charlotte). Then there was the wacky “Dragzacta,” which allowed fans to take part in pari-mutuel betting on weekly bracket races as they would at a horse track.

Mack was involved in a lot of drag racing.

Today, Mack has shared his memoirs with CompetitionPlus.com recalling his in drag racing. His latest offering is the second part of a two-part series regarding his time with the NASCAR Drag Racing series.

The fun part of being on the team was actually setting up races. That began in earnest for me that first winter when we chose a site in DeLand. FL, a few minutes from Daytona Beach to hold our first Winter Championsips. The plan was to find a warm site for eastern and mid-western racers to start their season and take advantage of the big racing crowd already in the area for the annual Speed Weeks leading up to the Daytona 500. We had two weeks of actual building time to convert an old World War II landing strip into a race track. Race for five days, and then tear it all down again in one week to turn the property back over to the local government.

Long time race promoter Ed Otto was recruited to assist in the project and working with Otto was truly a unique experience. He had obvious credentials and knew what he was doing most of the time, but sometimes it was difficult to understand his plan. For the lighting system he hired a company with two of those old arc searchlights used to look for enemy war planes in old movies and re-purposed as store grand opening attractions. He had them positioned just behind and on either side of the starting line pointing down the track. They generated an enormous amount of light — until the Top Fuel cars started smoking their tires or someone did a major burnout and it was like a shade was drawn over a window. I have no idea how the dragster guys ever saw where they were going. Coming back up the return road after aiming right into that bright light was another challenge.

Seating was needed for the fans and Otto came up with the brilliant idea of renting portable seating from the many touring circus groups that wintered in the area. We used their flatbed trailers that magically turned into tiered seating platforms for about 10 or 12 rows of actual folding wooden chairs. We lined both sides of the track with those contraptions and they worked quite well. The operating staff for the event consisted of a number of member track operators from the north who brought some of their employees with them.

To entice some of the thousands of stock car racing fans in town to venture out to see drag racing we staged a special match race between Richard Petty and Curtis Turner. We got the Chrysler racing rep to come up with a muscle car for Petty and the Ford guy to supply a performance car for Turner. The plan worked and a giant crowd turned out for the night we featured that match. I had to get the two drivers together to go over the plan and make sure they knew what we wanted them to do. Petty got there first and was a delight to work with. He instinctively understood the plan. Much later in the evening, after much worry if he was going to show up, a car weaved its way into the staging area where we had the two cars ready.. Curtis Turner literally poured himself out of the back seat and staggered over asking who was in charge of this circus. I was petrified. Turner and the good ole boys that brought him must have stopped at a local bar before coming to the track. They were all smashed and I thought that we were in big trouble. Turner could hardly stand, much less concentrate on anything I was trying to tell him.

After a few minutes of trying to shield him from everyone, including the brass from the insurance company, I called Witzberger on the radio and told him we were in trouble. When I explained the situation he said to sober him up and get him into the car. The show had to go on. I was scared to death that something really bad was about to happen on my watch. I also worried about putting Petty into the next lane against him even though they weren’t driving “real” race cars. I found Petty and told him my concerns and he just laughed it off. He said not to worry about Curtis. He said that he would be more worried if he was sober because he never saw him drive sober and wasn’t sure that he actually could. The race went on to the delight of the fans. I can’t document this, but I think that Turner may have registered the worst reaction time in the history of drag racing in that first round of competition.

All in all things went well with that first race until an unusual cold snap hit central Florida that night dropping temperatures into the low teens. I notice a lot of fires burning near the grandstands with people huddling around them to keep warm. Nice idea, I thought, until I realized they were breaking up and burning the expensive folding chairs we rented and had to account for following the race. I panicked at that thought and again had to bother the boss who was hobnobbing with VIPs. He said to do something. Don’t let them burn up our chairs. How do I stop a bunch of drinking and partying race fans from trying to keep warm? One of my helpers told me he remembered seeing a hand-made sign a couple miles from the track advertising firewood for sale. I told him to find a couple of trucks and run out to get as much firewood as he could carry and distribute the wood anywhere he saw fires burning. That took care of the immediate problem but not before a lot of very expensive chairs were destroyed. It turned out that staging an event like this was a lot more complicated than I originally thought. Lots of valuable lessons were learned.

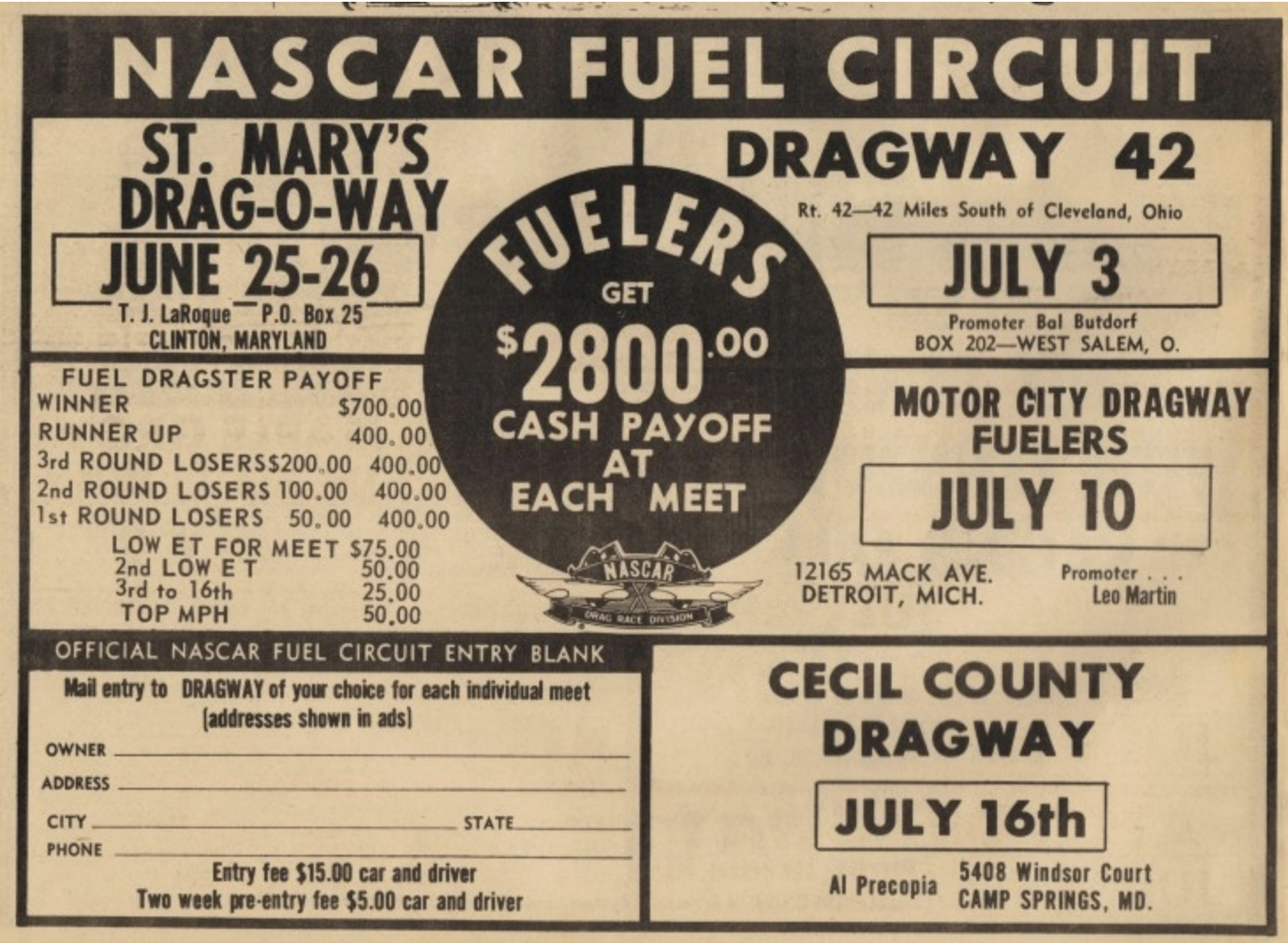

The season progressed reasonably well from there with the rest of our events held at existing tracks with competent staffs to assist us in staging the races. Major events were held at DeLand, FL, Richmond, VA, Niagara Falls, NY, Atco, NJ, Cecil County, MD, Union Grove, WI, Cordova, IL and Pittsburgh, PA. I felt that things went very well for a first season that culminated in our first National Championship held at Dragway 42 in West Salem, Ohio. By then we were attracting a lot of attention and great fields of cars. I remember the Top Fuel field filled with nationally prominent cars including the likes of Don Prudhomme in Roland Leong’s famed Hawaiian dragster and my favorite guy to work with Connie Kalitta. Kalitta, incidentally, became the only driver to ever win a Top Fuel Trifecta winning the NASCAR, NHRA and AHRA championships.

An interesting side story to the Nationals at Dragway 42 was a situation that developed when we had an entry with a dragster show up driven by a lady from upstate New York named Shirley Muldowney. Shirley had been embroiled in a battle with NHRA which refused to license a female driver at the time blaming an insurance issue. I was in charge of the licensing program, among all my other duties, so I had to handle this. I quickly called the insurance guy and asked for guidance. He hesitated for a moment and said that he saw nothing to prevent a female from being licensed to drive a dragster as long as she wasn’t pregnant. Well, we had a lot of certification and mechanical gadgets in our technical department but I didn’t think we had anything to test for pregnancy. I remember a very nice breakfast meeting with Shirley and her then husband Jack at a restaurant near the track in West Salem where I explained the situation. Shirley assured me that she was not pregnant and I had the unique privilege to sign and issue her first competition driver’s license. Fast forward five decades or so and it turns out that Shirley is now a neighbor living just a couple of miles from me in Huntersville, NC.

NASCAR Drag Racing was on a roll. The motorsports press was kind to us. The member track list was growing. Racers seemed happy. I was making lots of new friends along the way and the future looked bright. So what happened? Things slowly began to unravel and I began to sense a chink in the armor. I can never be completely sure of all the underlying reasons for the demise of the organization since I seem to be “the last man standing” of all the insiders and can’t ask their views now. Here, though, are my first hand observations and experiences during that interesting era.

I mentioned earlier that Ed Witzberger had a reputation of dealing with an iron fist and I respected that. As a mentor he taught me that if you are the guy making decisions about your business, make them decisively and stick with them. If you are paying the bills, you make the rules. Don’t allow your fate to be decided by someone with no skin in the game. As time went on I saw a disturbing pattern developing that went against the grain of that concept. At meetings and conference calls with promoters I watched Ed start asking them what they thought about ideas we were considering. This is completely appropriate as a tool to gather decision making information. Then he would completely surprise me by asking for a “vote” among the promoters to decide an issue or a policy. In most of those cases we had already thoroughly discussed the matter beforehand and were in agreement to tell the promoters what we were going to do. Here we were having them tell us what to do.

I had already learned that promoters, as a whole, were a group of strong individuals. They were usually successful in some other business that gave them the resources to jump into the racing business which was typically their hobby prior to that. In many cases the ‘hobby’ aspect was hard to shake and could cloud otherwise good business judgement. I pointed this out to Ed several times when he would take these votes.

I had already learned that promoters, as a whole, were a group of strong individuals. They were usually successful in some other business that gave them the resources to jump into the racing business which was typically their hobby prior to that. In many cases the ‘hobby’ aspect was hard to shake and could cloud otherwise good business judgement. I pointed this out to Ed several times when he would take these votes.

It started to consistently undermine a lot of work and planning that we had already put forth. I expressed some displeasure that he was turning his business into some sort of a democratic operation and putting our fate into the hands of people who didn’t know all the details of why we made certain decisions. I never got a satisfactory answer and he was, after all, the boss. I believe that this became a very corrosive element in the spirit and closeness of the group. Every promoter had his own axe to grind or idea on how he would benefit from any plan. When these open discussions got to the point of voting on what direction we would take on an issue I saw undercurrents of resentment among the key promoters developing.

Another issue that affected me personally arose during our work to put a good contingency plan together for the following season. I absolutely knew that companies who were interested in joining in that program were doing so because they had products they wanted to sell to our participants and fans. They normally had competitors selling the same product or service or why would they even need to energetically market with us? It was vitally important that we keep a level playing field for all the contingency sponsors within a given product area. That meant that we had to make a plan, set the price of the plan and the operating limits, then present it to all the businesses in that field. There was no room for negotiation after that plan was set.

The case in point that disappointed me involved the contingency plan for the many oil companies that wanted to partner with us. I had completed the plan and kept our pilot busy flying me around the country to seal the deal with those firms. I had just come back to the office from a harrowing trip in our plane to Oil City, PA, during a snow storm. I felt good about the deal at our agreed upon price and terms as well as our relationship with the oil company headquartered there when I got a call from Ed. He had just returned from a trip to Los Angeles for other business and was excited to let me know that he visited another oil company based in LA before coming home. He was exuberant that he just made a contingency deal for a figure almost 40% higher than I had just signed with my Pennsylvania client and several others the week before. I was livid. I told him that we had finalized the program, we all agreed to it and sold it to several companies already. He would just have to call that company and tell them that there was an error and we could not accept those terms. That would have given them a big marketing advantage over the other participants in the deal and we could not do that. Ed was dismissive about my concern and felt that if that company was willing to shell out more money, all the others could do the same. That may or may not have been true. We created a program that was acceptable to us and we already sold it to other clients on that basis. I was not about to go back to my previous clients and tell them the deal was off and now they had to pony up more money.

We were at something of a stalemate. The boss undermined me and now wanted me to clean up the mess. I didn’t want to do that and told him that he created the problem, not me, and he should call to fix it with the California company. Ed was not going to admit an error and said I had to fix it some way. He was the boss. He signed my paycheck and the iron hand was ruling. I recall that I felt the easiest way out was to call the company he made the deal with and explain that Ed was trying to be helpful and didn’t have the correct information with him at the time. After a few minutes of apologies they understood and agreed to the new numbers. I learned a valuable lesson about dealing with employees or people under your supervision that day. You better have their back and never overrule their decisions unless there is some very important reason to do so. You will never get their full backing or support again if you put them in that position.

Those two seemingly small examples may not be enough in themselves to sink a ship and probably were not. But they were symptomatic of other problems that were developing. All these little problems looked like they were working against the comfortable cocoon that Ed operated under in his other businesses and that he was used to. I knew that the venture was burning up cash at a pretty good rate and hadn’t gotten to the point where it could carry itself. I was not privy to how Bill France felt about the progress of the operation or what his tolerance was for watching money go out at the rate it was. I didn’t know his expectations either. That was beyond my pay grade.

I can remember specifically an event at the track that I would eventually come to own on its inaugural race and how expensive and demoralizing that was for NASCAR. Joe LaRoque, a very nice and hardworking man, desperately wanted to own a drag strip. He had a successful trucking and excavating business in Maryland and set out to build the biggest and best race track in the country. He asked me for advice and help in the design. He had only seen one or two local tracks. I suggested that he fly out to Bakersfield, CA for the big March race and get some ideas on what he wanted and we would go from there. In retrospect, that may have been the worst advice I could have given him. He came home with visions of grandeur and a plan to build a track that even the federal government wouldn’t have attempted. He took nearly all his trucks, equipment and employees off productive jobs and set them to work building his dream. .

He moved millions of yards of dirt and gravel to get the rough property into shape. In one spot he put in more than 100 feet of fill to make what is now the starting line. He trucked and spread enough asphalt to build a runway bigger than most municipal airports of the day. The track was more than 100’ wide and a mile long, not to mention entrance roads and pit areas, He spent every last dollar he had to build St. Marys County Dragway in Budds Creek, MD. for the opening day event he so much wanted. He made a deal to co-host the NASCAR Top Fuel National Championships with an unheard-of purse in a place no one ever heard of and probably couldn’t even find on a map at the time. He had a dream of another Bakersfield meet that would establish the track. Little did I know at the time that many years later I would become the owner of that track.

I began to worry as the event was less than a month away when I asked him about his advertising budget and which radio stations were in the buy. I was interested because I grew up in the nearby Washington, D.C. area and knew the market pretty well. He looked at me like a deer in headlights with an expression that clearly said he had no idea what I was talking about. He kept avoiding any answer. It was clear that he had no advertising budget. He did say not to worry, “Everybody” knows about the race. I was not at all involved with this particular race other than to make sure we had a big field of Top Fuel dragsters and run that portion of the event. The deal was between LaRoque and Witzberger and I fully presumed that Don Dillman was on top of the promotion end of things. None of us had any idea that he was completely out of money by the time he finished building the track.

The race was a success from the standpoint of a fantastic field of dragsters. The big purse made that part easy and we had already established a loyal following of good racers at our circuit events. Everything else spelled disaster and anyone there could see that. There was no-one in the stands and I doubt there were 100 other cars in the pits that hot and humid day. I drove to the main gate near the end of the day to see one of the saddest sights I can remember. LaRoque was sitting in a folding chair next to Witzberger with his face in his hands. Clearly a broken man whose dreams had just vanished. He gambled everything he had, and everything his creditors extended, on the success of this first race. It wasn’t just an “also ran”, It never left the gate! There was no money to pay the drivers, insurance, employees — nothing. I motioned Ed aside to ask how we should handle the drivers, He looked a little shaken, also, He handed me his checkbook and told me to fill out all the checks for drivers with the amount owed and bring it back to him. Ed paid for everything that day and I never saw Joe again. He never ran another race and the creditors foreclosed on the property.

The race was a success from the standpoint of a fantastic field of dragsters. The big purse made that part easy and we had already established a loyal following of good racers at our circuit events. Everything else spelled disaster and anyone there could see that. There was no-one in the stands and I doubt there were 100 other cars in the pits that hot and humid day. I drove to the main gate near the end of the day to see one of the saddest sights I can remember. LaRoque was sitting in a folding chair next to Witzberger with his face in his hands. Clearly a broken man whose dreams had just vanished. He gambled everything he had, and everything his creditors extended, on the success of this first race. It wasn’t just an “also ran”, It never left the gate! There was no money to pay the drivers, insurance, employees — nothing. I motioned Ed aside to ask how we should handle the drivers, He looked a little shaken, also, He handed me his checkbook and told me to fill out all the checks for drivers with the amount owed and bring it back to him. Ed paid for everything that day and I never saw Joe again. He never ran another race and the creditors foreclosed on the property.

I sensed Witzberger’s waning interest in the organization soon after that event and his visits to my end of the office became less frequent. I was never involved in the bookkeeping end of the business but I know the ledgers were in a sea of red ink. I was assured in the beginning that the financial end of things was not of great concern at the outset. Witberger and France were big boys. They knew it would take time to get a project like this on solid financial ground. I also knew I was working for two guys with very deep pockets. The atmosphere grew steadily more glum around the office by the third season. The excitement was gone. No one looked forward to those great brainstorming sessions anymore. The member track operators began asking questions about the direction of the ship and I was having difficulty coming up with answers.

I think I finally realized this project was not going to get better when Don Dillman stopped at my office to chat one day. He had been with Ed for many years and was really devoted to him. He asked if Ed had talked with me about how things were going recently and then opened up that he had never seen him like this since he had been working for him. It was almost as if he didn’t want to know anything about the NASCAR Drag Racing Division. It appeared to me that Don felt Ed was disenchanted because he was not used to failure and chose to ignore it was happening. Maybe denial is the right word to use. He didn’t have the fire and enthusiasm in the project any longer and chose to ignore it. I never asked France about it because it would not be my place to sidestep Ed to talk to him. I truly loved Ed Witzberger and admired him as a man and a leader. I was also very thankful for the faith he exhibited in me and what he taught me.. I felt that this situation was one that he had to work out for himself and decide how he was going to handle it. He was a very proud man and I respected that. He earned his right to be that way.

Meanwhile, I had to think about my own future and it was beginning to look like NASCAR would not be a part of it. I still knew my future would be in racing, though. I was talking with a track owner who was tired of working hard for very little and was interested in possibly selling or leasing his facility. It wasn’t much of a track, but I felt it had a reasonably good location and hand a chance to make it with some energetic promotion. I made a deal with Bob Grimm to lease the Mason-Dixon Dragway in Hagerstown, MD. but had very little capital to launch such a project. The lessons learned from France and Witzberger gave me the inspiration and courage to go to a company that specialized in operating concession stands at major events to see if they were interested in working a deal. Instead of the customary 25% to 30% royalty fee for rights to the concessions, I proposed a flat fee for the entire season up front. I had some history with the firm since they operated the concessions at several NASCAR facilities and they accepted the offer. It gave me the seed money to start my dream of having my own track. I was on my way. I gave notice to Witzberger explaining my situation and he was very gracious about it.

The organization did not begin another season and I don’t know for sure the exact mechanics of its shutdown. I can only speculate about all the real reasons that it folded. Based on my observations while I was there, I sincerely believe that the project ceased to be a challenge to Ed Witzberger and his interest waned when things did not go the way he wanted them to go. It wasn’t just the money to Ed. When he started feeling the wrath of some of the promoters who were getting impatient with him I think that affected his feelings. He needed to be the alpha dog and have the respect of his followers. He certainly had that in all his other ventures but this was different. I don’t remember seeing any pressure coming from Daytona Beach. I don’t think that played a big part because Ed was bankrolling most of the venture himself. My belief was that France looked at drag racing and Witzberger as just lending his name to it in the hope that it would pay a dividend if successful. I believe Ed just lost the fire in his belly for the project. I learned that when you are selling enthusiasm and you lose your own enthusiasm it shows very quickly. Ed lost that and those around him recognized it. That was another huge lesson I learned from the best mentor ever, whether he knew he was my mentor or not.